On the occasion of his first and major retrospective in Europe, it is worth exploring the legacy of enracinement and ouverture, a brand of cultural nationalism which underpinned Senegal’s policy of cultural diplomacy especially in the country’s glided age of the 1960s and in the first-half of the 1970s.

Introduction

Dakar-based El Hadji Sy is easily the most accomplished artist of his generation. His emergence in the 1980s came at a crucial moment in Senegalese art history when the state shifted from its prime role as the author and promoter of modern art in Senegal and artists took it upon themselves to redefine not only the basis of modernist art in Senegal but to chart new avenues for Senegalese art to thrive at an international level. Sy and a coterie of artists disavowed the institutional École de Dakar, a complex of modernist aesthetics hinged on a supposed return to African cultural roots and combined with the philosophical ideas of Négritude and pan-Africanism, officially promoted by the government. More importantly as cultural entrepreneurs, artists such as Sy began to collaborate with foreign cultural institutions, artist-colleagues, and multilateral organizations, on an individual basis. On the occasion of his first and major retrospective in Europe, it is worth exploring the legacy of enracinement and ouverture, a brand of cultural nationalism which underpinned Senegal’s policy of cultural diplomacy especially in the country’s glided age of the 1960s and in the first-half of the 1970s.

Understood as polarities of rootedness and internationalism, enracinement and ouverture also acted as a framework used by the state to present artists as Senegal’s cultural ambassadors. Artists were expected to create locally relevant art and, at the same time, to serve as vectors for a Senegalese vision of art modernity at an international level. Though this dialectical notion is no longer key to the enunciation of Senegal’s cultural policy, its residual effect, as an unconscious force, continues to shape the language of culture programmatically at the institutional level and artistic practice at individual levels, in a variety of ways. This essay maps the history and evolution of enracinement and ouverture, addressing the way the dialectical concept enables a richer understanding of artistic contemporaneity in Senegal. It focuses attention on the articulation of Dakar as a major cultural hub where the local and global collide captured in the Biennale de l'Art contemporain Africain de Dakar, arguably the most important platform for contemporary art in Africa. It also addresses how artists including Sy are able to position themselves as locally rooted artists with an international presence in the spirit of global contemporary art.

Enracinement and Ouverture Reconsidered: History and Context

It was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who suggested that parents must bequeath two things to their children: roots to give them a sense of home and belonging, and wings to see the world and to conceive of a self beyond the limitations of home, to contemplate other pathways of knowing and becoming. Senegal’s art history is replete with the iconic role of the poet-philosopher president Leopold Sédar Senghor who arguably invented or catalyzed Senegal’s modernist art and modernity based on his philosophy of Négritude. The art historians Elizabeth Harney and Joanna Grabski have variously addressed Senghor’s impact in molding the modernist consciousness of generations of Senegalese artists in the early postcolonial period. Senghor had a special relationship with artists who were described as chers enfant, children of the state. As the president, he was their benefactor and father, provided patronage, subventions, scholarships, and a salary. Senghor’s greatest bequest to his children, arguably, was the dual consciousness of enracinement and ouverture, a complex sense of being in the world which allowed artists to be planted firmly in their cultural roots and simultaneously demonstrate cosmopolitan aspiration. Senghor created a privileged social space for artists with the expectation that they would drive Senegal’s modern culture and put it on the international map. In other words, the artists would have roots and wings. It is therefore worth exploring the historical context of enranciment and ouverture which has helped to shape the artistic identities of generations of artists in Senegal in the early postcolonial period and which continues to define the creative consciousness of artists working today.

In his roles as president, cultural broker and art patron, Senghor believed in the development of a modern culture totally beholden to the new postcolonial reality.

After gaining political independence from France in 1960, successive Senegalese governments considered culture a key aspect of national planning, social development and economic prosperity. The tone was set by Senghor. As the first president of independent Senegal, he defined culture as the foundation on which national development and economic growth rests. [1] Senghor’s promotion of culture was part of a development aesthetic which encompassed his political, economic and social agendas. His cultural policy frameworks included the integration of cultural development in the economic and social development, the need to promote mass culture, and the incontrovertible guarantee of freedom and flexibility in creative work. It also included the integration of cultural heritage with science and technology, support for creativity in intellectual and artistic fields, and the protection of literary and artistic works. [2] Négritude was the ideological foundation of Senghor’s cultural policy. [3] Defined as the belief in a shared black heritage, it was also understood as the self-affirmation of black peoples.

In the 1930s, Négritude emerged as a response to European colonialism. Inspired by a demand for racial dignity and acknowledgment of the humanity and cultures of African peoples, its basic tenet was the rehabilitation of the collective image of the black race that had been diminished by slavery, racism, and Western imperialism. As students in Paris, Senghor from colonial Senegal, Aimé Césaire from colonial Martinique, and Léon Gotran-Damas from colonial French Guyana, addressed the crisis of identity. Négritude arose from their desire to overcome self-rejection, and to embrace assumed, imagined, and tangible cultural roots. Caught between Europe’s cultural turmoil and modernist anxieties following the First World War, and the “borrowed personality,” a term invoked by Lilyan Kesteloot, imposed on them by the French cultural policy of assimilation, Senghor and his friends felt culturally marginalized and the self-loathing that came with colonial conditioning. [4] The French policy of assimilation was introduced in the late nineteenth century to program the colonized toward adopting French customs, mannerism, and cultures in order to become civilized, and at least in theory, granted the rights of French citizens. [5] By garbing themselves in borrowed “Frenchness,” the colonized was no longer native or fully French. It was this split personality that caused great anxiety for Senghor and his friends.

The culmination of Senghor’s articulation of enracinement and ouverture in the first decade of his presidency independence was Senegal's successful hosting of the First World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966. The festival, which celebrated the influence of the black world on world cultures in a classical Senghorian sense, also served as a reminder of black people's perseverance over adversity in a decade during which many countries in Africa gained political independence.

Négritude thus arose from a desire to re-invent black subjectivity by making an idiosyncratic return to imagined origins. Senghor, Césaire, and Gotran-Damas sought to distill what they concluded were authentic qualities of the African person that derived from worldviews, systems of thought, natural environments, and expressive cultures. Though Négritude’s vernacular reclamation and acclamation of a rooted Africanness to mitigate the borrowed Frenchness has been heavily criticized in scholarship for what can be described as its romantic vision. It must be understood for what it was - a form of modernist self-fashioning. Its basic tenets were to rehabilitate and revitalize the image of Africa that was framed, to borrow from Joseph Conrad, as the “heart of darkness” in the Western imagination. In the beginning, Négritude was approached as a literary and aesthetic reprogramming and thus served the psychological and intellectual needs of emerging black elites in Paris seeking to define themselves as cosmopolitans, rooted in the cultures, consciousness, or experiences of their African background, yet open to a world that included French civilization.

When Senghor became the President of Senegal in 1960, he transformed and institutionalized Négritude to become a functional state ideology. The concept gave rise to an intensive and extensive development of a culture in Senegal in the 1960s and 1970s. It covered the aesthetic, cultural, political and economic development programs of the newly independent state of Senegal. In his roles as president, cultural broker and art patron, Senghor believed in the development of a modern culture totally beholden to the new postcolonial reality. This modern culture was based on a combination of indigenous cultural traditions and the best examples of external influences. Senghor, who was well schooled in Western Enlightenment thought, was reproducing the enlightenment logic of cultural relativism and universalism. He conceived of Senegal’s postcolonial cultural relativism as the dialectical notion of enracinement (rootedness) and ouverture (openness) but still shaped by the ideology of Négritude. With this dialectical idea, Senghor sought to draw upon an African precolonial past, recognize the accident of colonialism, and accept the hybrid condition of postcoloniality.

Enracinement was the rubric under which values, epistemologies, and traditional social frameworks could be engaged from a pan-African perspective. [6] Ouverture welcomes the inclusion of non-African or black traditions and systems. [7] Through enrancinement and ouverture, Senghor also saw Senegal as a source of modern culture and an important meeting place for world cultures with Dakar as the venue. The culmination of Senghor’s articulation of enracinement and ouverture in the first decade of his presidency independence was Senegal's successful hosting of the First World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966. The festival, which celebrated the influence of the black world on world cultures in a classical Senghorian sense, also served as a reminder of black people's perseverance over adversity in a decade during which many countries in Africa gained political independence. In pursuit of enracinement and ouverture, the festival positioned Senegal in relation to the world as a growing cultural hub open to international exchange.

Following the success of the 1966 festival, Senghor focused his attention on the role of Senegalese artists as agents of modern art for a country and continent hoping to secure a spot in the international arena of culture. Through their works, artists were expected to encompass traditional roles of the artist in precolonial times, as griots, as seers, as documentarians of social life, and at the same time serving the new and modern demands of a postcolonial Senegal. [8] As cultural ambassadors they were expected to secure a place in the international sphere of modern and contemporary art but firmly anchored in the discursive contexts of postcolonial modernity in Senegal. Senghor’s government instituted “Great Masters of Contemporary World Art,” “Salon des Artistes Sénégalais,” and Art Sénégalais d’Aujourd’hui, to further Senegal’s cultural policy objectives and enhance cultural diplomacy. “Great Masters of Contemporary World Art” was created in 1970 as a series of monographic exhibitions which introduced the works of the leading lights of international modern art movements such as Marc Chagall and Pablo Picasso to Senegal’s art community. [9]

Négritude was approached as a literary and aesthetic reprogramming and thus served the psychological and intellectual needs of emerging black elites in Paris seeking to define themselves as cosmopolitans, rooted in the cultures, consciousness, or experiences of their African background, yet open to a world that included French civilization.

The exhibitions presented the merits of enracinement and ouverture to modern Senegalese artists. [10] Chagall, for example, reflected his Hassidic background, Eastern European Jewish folk culture, Parisian avant-gardism, and primitivist fauvism in his work. Similarly Picasso's modernism reflected his Iberian roots, Parisian avant-gardism and the universal appeal of African art which he was drawn to. These exhibitions of international art stars were geared toward consolidating Senegal’s cultural diplomacy, one that positioned Dakar as a metropolitan cultural hub and brought Senegalese artists into dialogue with seminal figures of modern art. Senghor's inauguration of the annual Salon des Artistes Sénégalais in 1973 provided an important avenue to discover and foster emerging artists and subsequently inspired Art Sénégalais d’Aujourd’hui in 1974, a state-organized international travelling exhibition to expose modern Senegalese art to an international audience that circulated among several western venues for ten years. [11]

Zdj. 1 Dak'Art 2014, Wystawa międzynarodowa, Dakar, Senegal, 10 Maja - 9 Czerwca 2014. Zdjęcie i prawa: Lucie Falque-Vert

Dakar, Dak'Art, and Contemporary Senegalese Artists in the Global Contemporary

I want to turn our attention now to the cultural space of Dakar which serves as an interface between the local Senegalese and international art worlds. Dakar, the capital city of Senegal, is located at the tip of the Cape-Vert Peninsula on the Atlantic coast. It’s most famous district of Gorée Island once served as a slave-shipping point during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Anthropologist Hudita Nura Mustapha describes it as a world city that has been shaped by its legacy as the capital of Francophone Africa, the reinvention of local agendas by an astute consideration of postcolonial transnational cultural and urban processes. [12] Far removed from the infamy that trails several African big cities such as Lagos, Johannesburg, Nairobi, and Cairo, Dakar has gained a certain notoriety as a cosmopolitan pan-African city that is easy to navigate and is thus attractive to western visitors.

The defining character of Dakar is what I have referred to elsewhere as “communitarian solidarity”, the collective sense that dictates social consciousness and the urban fabric of the city, and which also shapes the relationship between locals and visitors. [13] For example, there is the social activity of eating together with bare hands from one platter of food to foster affection and community. This is reflected in the urban architecture where residential buildings are connected by or share walls so that you do not easily know where one building begins and another ends. There are also the Dakar Dem Dikk, the big blue buses that constitute the public transportation system, wherein commuters are stacked too close either seated or standing, but which evinces a Senegalese sense of collective self. As a gesture to community, younger commuters often offer their seats to older commuters who reciprocate by offering to carry their bags. It is this logic of communitarian solidarity that infuses the various cultural initiatives in Senegal since the independence of which the Dak’Art biennale, held in Dakar, is the latest and most visible in terms of scale.

A majority of the country’s artists live and work in Dakar and its surrounding suburbs. They are part of the enunciation of communitarian solidarity that dictates the city’s social world. They are also part of, and help to create, the local artworld ecosystem that reaches an apogee every two years during the Dak’Art Biennale, the biggest contemporary art event in Africa (fig. 1). During Dak’Art a critical mass of local and international visitors converge in the city to encounter the several hundreds of exhibitions staged in art institutions, private residencies, restaurants, artists’ studios, night clubs, restaurants, curio shops, gas stations, private galleries, public buildings, embassies and cultural centers, spread across Dakar and beyond. Mainly, I will explore Dakar as the venue of Dak’Art, focusing attention on how the biennale instantiates “glocality.” Biennales are generally understood as sites where the local embraces the global and vice versa. For Senegalese artists, Dak’Art provides a venue to reconcile homegrown and international art discourses. It puts them into the conversation and brings them in contact with the networks that comprise the international art mainstream. In the more than twenty-five years of its existence, Dak’Art has served as an important manifestation of enrancinement and ouverture.

In the mid-1970s Senegal's economy began to falter. By 1980, Leopold Senghor was forced to retire and installed his protégé Abdou Diouf in his place, a trained economist and technocrat, who became president in 1981 in a period racked by economic depression. This scenario affected Senegal's modernist vision of arts and culture as crucial to national development and the role of the artist as a cultural ambassador. The innovative “Great Masters of Contemporary World Art” was discontinued as Senegal’s economy declined, as were the annual salon exhibitions. They had remained sporadic until the last one in 1977 though the annual salon would later be re-established in the 1980s, this time driven by the artists themselves and not the state. The new economic reality lowered the priority previously assigned to cultural initiatives during Senghor’s presidency.

Concomitant with the realism of the depressed economy of the 1980s; Senegalese artists began to seek new opportunities beyond the ambit previously provided by the state. A majority that came of age professionally in the period, such as El Hadji Sy, began to disentangle themselves from the institutional École de Dakar aesthetics, which the state has championed as a distinct Senegalese modernism. A generality of post-independence Senegalese artists trained at the École des Beaux Arts, the premier national art school, in Dakar, and evinced a codified aesthetic vision that drew upon Senghor’s Négritude philosophy and pan-African cultural politics. École de Dakar, understood as the most important post-independence art movement in Senegal, came under criticism in the mid-1970s for what was perceived to be a stifling and prescriptive approach to the questions of aesthetics. By the 1980s combination of factors including the economic climate and a shift in aesthetic ideology impacted its hold on the artistic imagination in Senegal.

As a member of the iconoclastic Laboratoire Agit’Art and through his Tenq initiative in the period, El Hadji Sy was very involved in the attempts to shift the language of Senegalese modernism away from the institutionalized École de Dakar. Established in the late 1970s, Laboratoire Agit’Art was a collective of visual artists, filmmakers, writers, performers and musicians, active in creating a social space and rethinking the artist studio as a laboratory in which ephemerality and performance took center stage. Similarly, Tenq, which Sy co-founded with the artist Ali Traore, was conceived as a non-conformist and democratic space for the creation of art, exhibitions, film screenings, and discourse on artistic process, pedagogy, art appreciation, and criticism with a focus on returning art to the public. Even more significant was Sy’s role as the president of the Association Nationale des Artistes Plasticiens Sénégalais (National Association of Senegalese Visual artists) during its formative period from 1985 to about 1987. In his capacity as the president of ANAPS, Sy facilitated many public and private exhibitions, and numerous international exchanges. [14] He was also involved in the book project Anthology of Contemporary Fine Arts in Senegal, as the co-editor with Friedrich Axt, a project begun in 1984 and completed in 1989 with the financial support of the Museum of Ethnology (now the Museum of World Cultures), Frankfurt.

The inaugural Dak’Art, which opened on December 12, 1990 at Place de l’Obelisque, the grand parade ground in Dakar, was a literary festival.

One of the most important exhibitions organized under Sy’s watch was the Dakar version of the international travelling exhibition “Artists of the World against Apartheid” that was first staged in Paris in 1983 as part of the global anti-Apartheid campaigns with the support of the “United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid.” [15] The Dakar version titled Art contre l’Apartheid was a context for Senegal to show solidarity with South Africa’s liberation struggle in the spirit of pan-African unity. In his opening address at the exhibition, Sy berated the government for its failure to fulfill its cultural mandate as required by the constitution. A reprimanded President Diouf reiterated his commitment to arts and culture as was the case during the presidency of Senghor. Significantly, the exhibition as well as succeeding exhibitions during the latter-half 1980s laid the groundwork for the Dak’Art biennale to emerge subsequently. Instructively, the government’s announcement of the creation of Dak’Art in 1989 was during the annual salon. [16] When Dak’Art was finally created, artists including El Hadji Sy, Issa Samb, Fodé Camara, and Souleymane Keita who were part of Laboratorie Agit-Art or Tenq featured prominently in its technical, orientation, and organizing committees. These artists were all actively involved in the goal for an international forum in Senegal in either personal capacities or through collective actions.

Over the years Dak’Art has launched both Senegal and African artists into international reckoning on the basis of its unique mandate to serve as a mainstream venue for contemporary art from a pan-African perspective and to leverage on its visibility to insist on the viability of the practices of African and African diaspora artists. The emergence of supranational regions as power blocs in the international art world favored the proliferation of art biennials. Often established in pursuit of diverse agendas by different countries, biennials either project themselves as emerging centers of cultural power by weaving together the symbolic values of art, commerce, and diplomacy, or claim to chart alternative models of cultural representation that place emphasis on local conditions, geopolitics, and the individuality of artists as citizens of the world. They all have a common interest in connecting their host countries or regions to the international circuit of contemporary art.

The inaugural Dak’Art, which opened on December 12, 1990 at Place de l’Obelisque, the grand parade ground in Dakar, was a literary festival. This was because the biennale was initially planned to alternate between literary and visual arts as a partial gesture to the nostalgia of the First World Festival of Negro Arts of 1966 and in honor of Senghor who was a literary person. The focus on literature however did not have the desired impact for the state which had hoped to use it to re-establish Dakar as a cultural focal point. The 1992 edition of Dak’Art was a much bigger event and focused strictly on visual art though accompanied by music concerts, performances, and conferences. The exhibitions were in multiple venues spread around Dakar. This approach would expand in succeeding editions of the biennale, thus helping to place art and visual culture in closer proximity to everyday people at each edition of the art festival. More importantly, Dak’Art 1992 which was based on the national pavilion model in theory though not in the actual manifestation of its exhibitions. It was the first real attempt to give heed to the call by Senegalese artists for a platform for international artistic exchange. By 1996, Dak’Art once again re-jigged its strategy and institutional identity to focus mainly on artists of African-descent for its official exhibitions although still allowing room for non-African artists to participate. Its re-invention as a pan-African biennale was borne out of the need to distinguish itself from a proliferating field of art biennales and yet remain true to its cause of providing that platform of visibility for marginalized African and African diaspora artists in the international mainstream. This particular vision has remained in force but adapts to accommodate the curatorial proclivities of the different curators that have managed the biennale since then.

From its humble beginnings in the early 1990s Dak’Art has become one of the most highly anticipated events in the international art calendar. Its development mirrors the expansion of the international mainstream beyond the Western hemisphere and growing acceptance of non-western artists as some of the important artists working today. It has provided a unique context of re-imagining Senegal’s territorial sovereignty as transnational, and the host city of Dakar as cosmopolitan, international, and pan-African during its many iterations. That sense of critical locality and international vision otherwise which underpin Dak’Art comes through in the work of a number of contemporary Senegalese artists. Soly Cissé and Ndary Lo are two prime examples. The two have featured in multiple editions of the biennale. Through their individual practices, it is possible to gauge the impact of the biennale as a platform that mediates the international careers of local artists. In Ndary Lo’s case, he won the biennale’s grand prize on two occasions in 2002 and 2008. Cissé and Lo live and work respectively in Mermoz in the heart of Dakar and its adjoining suburb of Rufisque.

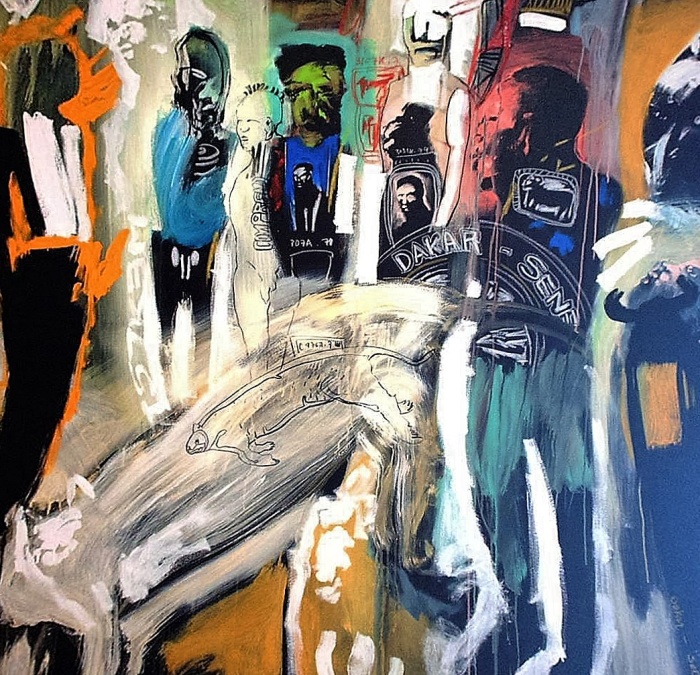

Serie Colorée also includes the legible numberings that have come to symbolize contemporary consumer culture in Cissé’s work, which he refers to as urban signs. “Dakar – Senegal” is clearly inscribed on the first panel in the triptych to outline the sociological and physical space that is the subject of Cissé’s attention.

Cissé’s work is typically a natural extension of himself, even though his subject matters often consist of explorations of human conditions at various levels: local, national, pan-African, global, and universal. His work reflects the artist’s search for self-actualization, but bears the pensive and fractured marks of his urban experiences in Dakar and the various world cities where his international career has taken him. His aesthetic comprises a wide range of cultural references – the everyday experiences in his birthplace of Dakar, his Wolof roots and an assemblage of other cultural traditions of Senegal, the legacy of French colonialism, and his engagement with the circuits of the global art world. His cosmopolitan consciousness, of which Dakar is the center of gravity, dictates a familiarity with the worldwide flow of electronic information, what Arjun Appadurai refers to as a “mediascape,” which Cissé described as a world of visuals during our conversation in Dakar in May 2010. Cissé scavenges this world of visuals for inspiration and creative fodder to navigate complexities and interconnectivities that define his world.

Consider for example Serie Colorée (fig. 2. 2010, acrylic on canvas), in which Cissé attempts to capture the intensity of Dakar. Typical of his work, the painting is composed of outlines and distorted forms, mostly of nude and clothed humans and animals, morphing into one another. These forms are realized in a combination of warm and cool colors, and of graphic, geometric and organic shapes, set against a flat picture plane. Serie Colorée also includes the legible numberings that have come to symbolize contemporary consumer culture in Cissé’s work, which he refers to as urban signs. “Dakar – Senegal” is clearly inscribed on the first panel in the triptych to outline the sociological and physical space that is the subject of Cissé’s attention.

Zdj. 2. Soly Cissé, „Serie Colorée” [tryptyk], 2010. Media mieszane na płótnie, 150 x 150 x 3. Zdjęcie: Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi. Prawa: Soly Cissé.

Zdj. 2. Soly Cissé, „Serie Colorée” [tryptyk], 2010. Media mieszane na płótnie, 150 x 150 x 3. Zdjęcie: Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi. Prawa: Soly Cissé.

Zdj. 2. Soly Cissé, „Serie Colorée” [tryptyk], 2010. Media mieszane na płótnie, 150 x 150 x 3. Zdjęcie: Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi. Prawa: Soly Cissé.

For Cissé, Dakar is also a stand-in for other world cities that share similar experiences and rhythms of the everyday. One work that connects the specificity of Dakar to a more global reality is the installation Salon Inondé (Fig 3. 2010) which tackles environmental concerns. Parts of Dakar including the area where Cissé lives experience flooding during the rainy from June to about October. It is an existential experience for many Dakarois (Dakar locals) who populate the ghettos, and brings to mind the precarious nature of existence in most postcolonies. Cissé creates a compelling setting of a half-submerged living room. There is the unmistakable aura of human presence though the corporeal confirmation is lacking. Except for a table bearing two beer bottles and three cups, and a chair, the room is bare. The setting suggests a moment after the individuals who had been drinking have exited the room. The legs of the table and chair are cut and inclined at angles on the mirrors to give the impression of partial submersion and placed on twenty-four tightly aligned mirror panes. The reflecting mirrors create a trompe-l'œil effect of a never-ending visual depth, which pulls the viewer in. Cissé recreates experiential situations to convey the propinquity of inundation and to contextualize its social and economic effects on everyday people. He does this by using interrelating signs and symbols, both for their emblematic and material content, to create a hyper-real world of those affected by flooding. Both Serie Colorée and Salon Inondé were included in a joint exhibition by Cissé and Cameroonian artist Barthélemy Togou which was titled Objets noyés et bribes de vies, organized by the French Institute’s Galerie Le Manége, Dakar, under the auspices of Dak’Art biennale in 2010.

On his own part, Ndary Lo works mostly with salvaged materials from the urban environment. He examines the social contract between the artist and his surroundings. Lo’s aesthetic approach, known in local parlance as récupération, is a strategy that evolved in the 1980s in Senegal as artists, struggling with a lack of economic means to purchase conventional art materials, began to source alternative materials found in the urban environment. As Joanna Grabski argues, “Récupération signifies not just a locally specific discursive field; it is also positioned as ‘the new African installation’ admired for its ‘authentic’ interpretation of African artistic traditions in which incorporative sculpture and the accumulation of objects were common visual strategies.” [17] In the 1990s when Lo emerged, récupération had gained considerable acceptance as an important artistic technique, embraced by leading artists such as late Moustapha Dimé and Viyé Diba. A committed pan-Africanist, Lo’s oeuvre is layered with social messages aimed at multiple audiences: the immediate Dakar and Senegalese public, Africa, the Black world, and the rest of the world.

In 2002, he created La Promenade longue pour Changer (fig. 4), which won the ‘Grand Prize of Leopold Senghor,’ Dak’Art biennale’s top prize, in 2002. The installation, a visual manifestation of Lo’s new social vision for Africa, comprises several highly schematized human forms made out of rebar, a material used conventionally as a tensile device in building constructions. The human forms march in files along paths strewn with salvaged rubber slippers. The rebar formed from carbon steel is a tough material that suggests longevity, strength and purpose. These are ideal qualities Lo believes Africans should possess in the march toward productivity and development. The medium allows Lo to create a minimalist style that highlights brevity of form and verticality, with message and meaning residing in both the medium and the realized form. The installation may well have been inspired by Nelson Mandela. In 1995, Mandela, the revered freedom fighter published his autobiography under the title of Long Walk to Freedom, a year after he became the first black president of a democratic South Africa. The book which details Mandela’s trials, tribulations, and triumphs was meant to serve as a moving story of forgiveness, reconciliation, and change in a new South Africa. One needs look no further to comprehend why the book could have potentially served as a potent reference for Lo, given his constant emphasis on hope and perseverance.

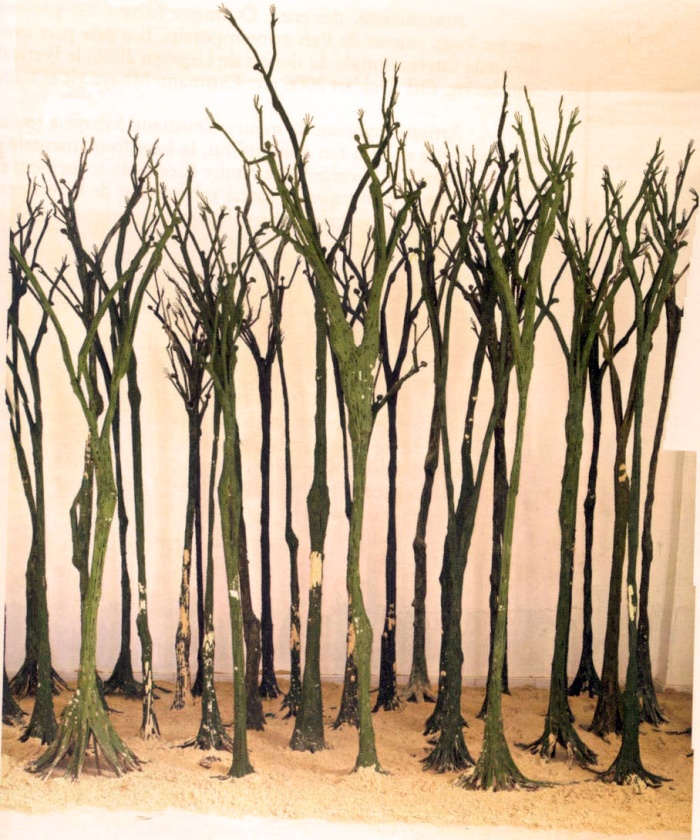

Zdj. 5. Ndary Lo, „Zielona ściana” [La Muraille Verte], 2006-2007. Instalacja w ramach Dak'Art 2008. Prawa: artysta i Dak'Art Biennale.

Zdj. 4 Ndary Lo, „Długi marsz do zmiany” [La Longue Marche du Changement], 2000-2001. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Zdj. 3. Soly Cissé, „Zalany salon” [Salon Inondé], 2010. Media mieszane, instalacja. Zdjęcie: Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi. Prawa: Soly Cissé.

Lo’s massive installation La Muraille Verte (fig. 5, 2006/2007) is another work that simultaneously address a local and global audience on the strength of its powerful social and environmental messages. The installation, which was jointly awarded the top prize of Dak’Art 2008, was inspired by Nigeria’s former President Olusegun Obasanjo, who, while on an official state visit to Senegal to attend the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) meeting, called for a concerted effort to tackle desertification and ocean surge in Africa through public awareness campaigns and tree planting. La Muraille Verte consists of several trees fashioned out of rebar and painted green, arranged on a pile of austere beach sand. Stripped of leaves to denote a lack of foliage, the impoverished branches of the trees are shaped into wiry, elongated, and contorted human forms, possibly to remind us of the role of human activities as a principal vector of environmental degradation. Yet Lo’s combination of plants and human forms also indicate the complexity that foregrounds human beings as a composite of nature. They are both force and matter reshaping the environment yet remaining vulnerable subjects of the environment. The physical space, from which African artists create, is often a space of poverty but rich in context-driven and socially-engaged messages. It is a space that mirrors both the struggles and triumphs of Lo and a majority of artists in Africa, operating within an economic zone of small means yet creating big art that tells the story of Senegal, Africa, and universal human stories from multiple perspectives.

It is important to stress that Dakar and the surrounding environs remain an artistic trope for many artists in Senegal and is not limited to Lo or Cissé. [18] Ibrahim Niang, Ndoye Douts, Fally Sene Sow, and Cheikh Ndiaye, are some of the artists who have made the variegated quotidian realities and visualscapes of the city central to their individual practices but are not discussed in this essay due to space constraint. Like Lo and Cissé, these artists have either participated in Dak’Art’s official or independent exhibitions. They all travel internationally and through their works highlight a "glocal" imaginary. Yet both Cissé and Lo, more than any other artists of their generation and those following, evince the entrepreneurial proclivity that clearly marked the El Sy generation in the 1980s. It can be argued that the two artists serve as a link between the old guard, their successors and the younger generation. Cissé and Lo embrace the cultural ideology that insists upon Dakar or the local context as a site of engagement but with global frames of reference, a vision pursued and enacted by El Sy and his cohort in their heydays.

Quite early on, Leopold Sédar Senghor, an intellectual giant and Senegal's first president, theorized the idea of universal civilization. Senghor believed that the greatness of civilizations is based on their mixed and interdependent nature, that is to say, their ability to draw concretely and creatively from multiple cultures.

Concluding Remarks

In the essay "From Art World to Art Worlds," Hans Belting and Andrea Buddensieg allude to a new kind of contemporary art that began in the 1990s which acts globally and is unburdened by the modernist legacy and its colonial history. [19] The language of global contemporary has been steadily deployed in the last few years in recognition of simultaneous coevalness and the multiple contemporaneous worlds of our present time. [20] Though the question of whether global contemporary truly provides a democratic vision of artistic contemporaneity or still retains the old western hegemony but by other means remains pertinent, [21] I am more concerned with the articulation of national identities and its intersection with artistic consciousness on the one hand, and the intensification of encounters and tensions between cultures, ethnicities, and different forms of social identities, brought about by globalization on the other. [22] The country of Senegal and her artists provide an excellent insight.

Quite early on, Leopold Sédar Senghor, an intellectual giant and Senegal's first president, theorized the idea of universal civilization. Senghor believed that the greatness of civilizations is based on their mixed and interdependent nature, that is to say, their ability to draw concretely and creatively from multiple cultures. World cultures, he argued, must contribute to an all-encompassing universal civilization based on symbiotic relationships and mutual respect for one another. [23] Senghor's position is not without criticism. Given his interest in fashioning a response to the French mission civilisatrice, he was less interested in the aura of commodity and presented a romanticized vision of cultural capital. Yet it can argued that he was far ahead of his time in terms of moving the conversation beyond the universalizing logic of western modernity and the dogma of postcolonialism, and perhaps, also, anticipating the conditions that we now describe as global contemporary.

The occasion of El Hadji Sy's first career retrospective, though occurring outside of Senegal, provides a significant moment of reflection. His exhibition follows in the heels of the recent travelling international monographic exhibitions of African-born artists such as Ibrahim El Salahi's major retrospective at the Tate Modern in 2013 and El Anatsui's several simultaneous solo exhibitions at elite venues since 2011. All these point to a growing willingness to acknowledge the contemporaneity of artists who live and work in Africa. Yet it is worth asking whether the increasing monographic exhibitions of African artists in major western institutions do not in themselves manifest an emerging form of cultural cooptation which reinforces as opposed to challenging the West’s position as the gatekeeper and site of validation for the artist (western and non-western alike) in this age of global art.

BIO

Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi is an artist, art historian, and curator of African art at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College. He holds a B.A. in Fine and Applied Arts from the University of Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria, a postgraduate diploma in Museum and Heritage Studies from the University of Western Cape, South Africa and a Ph.D. in Art History from Emory University. He has curated major international exhibitions including the Dak’Art Biennale. His recent curatorial projects include Eric Van Hove: The Craft of Art (2016), Inventory: New Works and Conversations around African Art (2016), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (2015), Auto-graphics: Works by Victor Ekpuk (2015), Ukara: Ritual Cloth of the Ekpe Secret Society (2015), and The Art of Weapons (2014–15). Nzewi has lectured widely and participated in symposiums in major academic institutions, museums, and biennale platforms in the United States, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

*Cvver photo: Dak’Art 2014, International Exhibition, Dakar (Senegal), May 10 – June 9, 2014. Copyright: Lucie Falque-Vert.

1. Mamadou M’Bengue, Cultural Policy in Senegal. (Paris: Seyni UNESCO, 1973), 20-21.

2. Ima Ebong, Negritude: Between Mask and Flag – Senegalese Cultural Ideology and the École de Dakar, in Africa Explores: 20th Century African Art, ed. Susan Vogel, (New York and Munich: The Center for African Art and Prestel, 1991), 198-209.

3. Leonard Irving Markovitz, Léopold Sédar Senghor and the Politics of Négritude (New York: Atheneum, 1969).

4. Lilya Kesteloot, Black Writers in French: A Literary History of Negritude, trans. Ellen Conroy Kennedy (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1974), xvi.

5. Diouf, French Colonial Policy of Assimilation, 1998.

6. Léopold Sédar Senghor, The Foundations of “Africanité,”or “Négritude” and “Arabité. trans. Mercer Cook (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1971), 7-8, 83-88.

7. Leopold Sédar Senghor, Discours d’Ouverture du Colloque sur la Littérature Africaine d’Expression Française (Mimeo, N.P, 1963).

8. Tracy D. Snipes, Art and Politics in Senegal, 1960-1996 (Trenton, NJ and Asmara: Africa World Press, Inc, 1998), 25.

9. M’Bengue, Cultural Policy in Senegal, 44.

10. Leopold Sédar Senghor, Allocution prononcée a l’ouverture de l’exposition Marc Chagall, Dakar, jeudi 18 mars 1971, (Dakar: Présidence de la Republic).

11. The exhibition opened at Grand Palais in Paris from April 26 until June 4, 1974, before traveling to several world cities that included: Paris, Nice (1974), Helsinki (1974), Vienna (1974), Stockholm (1975), Rome (1975), Florence (1975), Bonn (1976), Mexico City (1979), Washington DC (1980), Boston (1980), Massachusetts (1980), Hamilton, Canada (1980), Atlanta (1980), New Orleans (1981), Quebec (1981), Chicago (1981), Brasilia and São Paulo (1981), and Rio de Janeiro (1982). Djibril Tamsir Niane, “The Exhibitions of Senegalese Contemporary Art Abroad,” in Friedrich Axt and El Hadji Moussa Babacar Sy (eds), Bildende Kunst der Gegenwart in Senegal = Anthologie des arts plastiques contemporains au Sénégal = Anthology of contemporary fine arts in Senegal (Frankfurt am Main: Museum für Völkerkunde, 1989), 83.

12. Hudita Nura Mustafa, “Practicing Beauty: Crisis, Value and the Challenge of Self-Mastery in Dakar, 1970-1974. (Ph.D: Diss., Harvard University, 1998), 30-31, 34.

13. Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, “Dak’Art as a Performative Site of the Common,” in 11e Biennale de l’art Africain Contemporain, Dak’Art 2014. (Dakar: Dak’Art Biennale Secretariat. 2014), 28-30; 31-33.

14. In the 1990s, Sy was involved in a very ambitious project as the co-curator of the seminal traveling exhibition “Seven stories about Modern Art in Africa” at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (27 September – 26 November 1995) and Malmo Konsthall Malmo, Sweden (27 January – 17 March 1996).

15. The international traveling exhibition included works by 80 leading international artists from different geopolitical regions including Magdalena Abakanowicz (Poland), Gavin Jantjes (South Africa), Iba Ndiaye (Senegal), Skunder Boghossian (Ethiopia), Robert Rauschenberg (USA), Twins Seven Seven (Nigeria), Sol LeWitt (USA), Julio Le Parc (Argentina), Patrick Betaudier (Trinidad and Tobago), Wau-ki Zao (China), Jesus-Raphael Soto (Venezuela), Mario Gruber (Brazil), Wilfredo Lam (Cuba), Valente Ngwenya Malangatana (Mozambique),Titina Maselli (Italy), Roberto Matta (Chile), Jean-Michel Meurice (France), Pedja Milosavljevic (Yugoslavia), Robert Motherwell (USA), Pierre Soulanges (France), Klaus Staeck Germany, Saul Steinberg (Romania),Yasse Tabuchi (Japan), Emillio Tadini (Italy), Antonio Tapies (Spain), Joe Tilson (England), among others.

16. Abdou Sylla, Arts plastique et état au Sénegal: Trente-cinq du mécénat au Senegal (Dakar: IFAN, 1998), 148.

17. Joanna Grabski, “Urban Claims and Visual Sources in the Making of Dakar’s Art World City,” Art Journal No. 68 Vol. 1(2009): 9.

18. Grabski, “Making of Dakar’s Art World”, 1-15.

19. Hans Belting and Andrea Buddensieg, From Art World to Art Worlds. In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds, ed. Hans Belting, et al. (Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM/Center for Art and Media; Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2013), 20-27.

20. Marc Augé, An Anthropology of Contemporaneous Worlds, (Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, 1999).

21. Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Empire, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000).

22. Peter Weibel, Globalization and Contemporary Art. In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds, eds. Hans Belting, Andreas Buddensieg and Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM/Center for Art and Media; Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2013), 20-27.

23. Markovitz, Politics of Négritude, 330-31,145-152,158-159.