I always say that you cannot tell what a picture really is or what an object really is until you dust it everyday.

Getrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

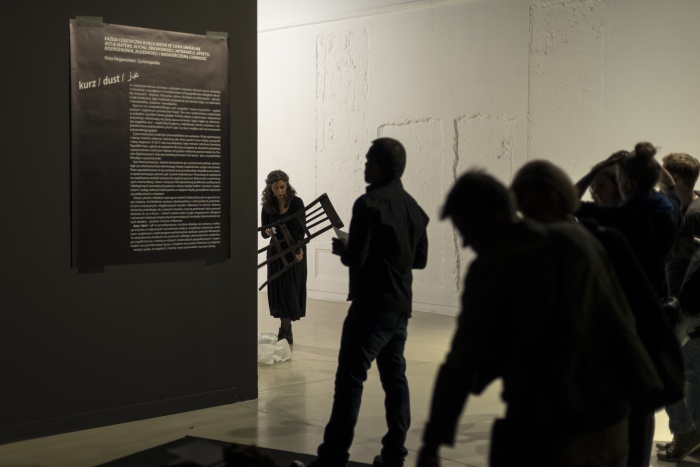

In 2015, as part of the exhibition dust/kurz/ghobar, Neda Razavipour’s performance Travelling Pieces took place. Along with the performer, carefully packed objects with airline labels arrived in Warsaw. These were “Polish chairs,” “silver-plated vessels from Warsaw,” “Polish mirrors,” “Polish crystal.” The unpacking, dusting, and arranging of the objects in space resonate with the echoes of the journeys that these objects had undertaken in order to find themselves in Iran and bring post-images of the reminiscences of the Polish emigrants at the time of the Second World War, the fair-haired children covered in soot and dust; these are intertwined with the reality of today’s Iran, in which the “great dust” is all-pervading; the air in Teheran is among the most polluted in the world. The relationships between the scenes, associations, and events are ephemeral and subtle, mediated by the objects, material, and tangible.

The exhibition, of which this performance is a part, explores the symbolic potential of dust – or perhaps dust and ash, to bring into play the ambiguity of the multilingual title. Let us consider it for a moment: dust piles up, swirls and covers surfaces – old and no longer visited; ash is powdery and ephemeral. Both dust and ash can bring irritation. Dust lingers and irks, imposing itself but also reminiscent of passing away, things “turning to dust.” So does ash: “ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” Dust is a substance that belongs to the forces of chaos; it is all-pervading matter, with layers of small particles. A cloak of dust wraps itself round objects but also hides and distorts them. It is a powder that settles discreetly and silently on things and places that we pass by, beyond the zone of our regular, daily activities. In Jolanta Brach-Czaina’s ground-breaking book Cracks in Existence, the fight against dust and the restraining of its silent offensive through our constant busyness has been one of the mechanisms of supporting the human world, an element in its invisible logistics. This is also the approach to dust adopted by Maria Pinińska-Bereś in her performance The Woman with a Ladder, focused on keeping busy, tidying, and sweeping up. As Brach-Czaina points out, such everyday chores, which she palpably exposes, are culturally the domain of a woman – and as such, invisible work. It is not for nothing that female artists have taken this message on board.

Perhaps this “metaphorical dust” that obscures old memories is disorienting, or its particles fall apart, blurring the image. This is also what Travelling Pieces talk about. Neda Razavipour’s performance brings back memories; it is revealing. The unpacking of the “Polish” objects has become the means for extracting the non-apparent information – a metaphorical unpacking, or dusting off, of forgotten images and fragmented knowledge. Once unpacked, the objects assume new roles, becoming props in specific parts of the performance, presented during the three-month long exhibition. When the performer invites viewers to join in the game of “hot chairs,” in the background there appear stills from Khosrow Sinai’s film The Lost Requiem, with the soundtrack of an old Polish folk song, sung in Polish by the protagonists of his documentary, “Goń stare baby, goń stare baby, goń stare baby do lasa” (“Keep chasing old women into the woods”). Sinai, intrigued by an epitaph in an unfamiliar language, with the help of the cemetery caretaker – the custodian of the memory of the Polish civilians who came to Iran with Anders’ Army – has reconstructed a part of history that he had not been aware of previously. He tracks down the Polish men and women who spent part of their childhood in places such as Esfahan, the “city of Polish children,” both those who chose to stay on and those who decided to live their life elsewhere. In the reminiscences of the upper-class women from the generation of the director’s mother there often feature Polish women, who act as beacons of the European cultural model and fashion for the Iranian social class in the fast lane to Westernization. In Travelling Pieces, there is also a post-image of a memory from 1942, but with a different ambience: newly arrived Polish refugee children, their faces covered in soot and dust.

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Strangely, this part of history seems to have been mostly, and symbolically, put under wraps – it requires regular dusting. The dusting is necessary in order to uncover the “memory of things.” According to the concept of Jan Assmann, this is one of the components of cultural and social memory: objects – through their usage, the relationships they enter into with people and their functioning not only as implements but also as symbolic objects and the matter of our ambitions, dreams, and hopes – are a conduit for the reality of human existence in any given time. A few years ago, in Esfahan, a collection of glass negatives from the photographic studio of Abolqasem Jali was discovered. Parisa Damandan, photograph and curator, searched for negatives hidden at the time of the Islamic Revolution out of concern that they might breach newly imposed laws. These negatives, stored for decades in a disused warehouse, depicted the reality of the Polish community in Esfahan; they had been waiting to be unpacked and dusted, both literally and symbolically. Khosrow Sinai had no idea who the people were whose names were written on the tombs in his home village. He shot the footage for The Lost Requiem in 1983 and the production of the documentary took over a decade – during which time the Iranian government changed, and in the new regime of the Ayatollahs the film was, for a time, shelved due to censorship. In Poland it was shown much later. The next chapter of the story was due to coincidence: 2015 – when the exhibition dust/kurz/ghobar took place, was also a year in which attitudes to refugees deteriorated dramatically in Poland. The social mood turned against newcomers. The performance of the Iranian artist, which draws on the – significantly – forgotten and retrieved episode from the refugee history of the Polish nation provided an unexpected and subtle commentary on topical events.

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Images evoked from memory often seem random and ephemeral like dust. In the collective memory of the Iranians the two narratives, in which household objects of design serve as anchors – one of the early 20th century Polish engineers and entrepreneurs and the other, of wartime refugees – are often fused together. The facts are obscured by the better-known history and by that which appeals more to our emotions, hence Sandali-ye Lahestani (صندلي لهستاني) – “Polish chairs” – have been surrounded by a legend that goes back to the Second World War, and it is widely believed that this is how they had arrived in Iran. This association remains strong to this day; a new poster, which advertises the showing in Teheran of The Lost Requiem and The Remembered Requiem by Dorota Latour, a documentary about Sinai’s film, shows a Polish bentwood chair, taken apart.

The everyday utilitarian and decorative objects selected by Neda Razavipour function in Iran as artefacts associated with Poland; they enjoy a parallel life that we have not been aware of in their country of origin. Lahestan, as Poland is called in Persian, is a key word in Iran’s antiquarian market. The “Polish chairs” are classical Thonet bentwood pieces of furniture, made in Jasienica and Radomsk. The most popular is model no. 14, with its characteristic, semi-circular back, although this number has also sometimes been used to refer to the familiar bentwood rocking chairs. The household name – “Polish chairs” – has nostalgic connotations. Neda Razavipour says that they are a favorite item of interior design for stylish Teheran cafés and vintage-style apartments. They were already present in Iran before World War II. Even before that, Polish engineers and businessmen had travelled to the country that was undergoing modernization, bringing new designs, technology and also machinery, helping to develop the railways and industry, for example the glassworks – the popular glasses for drinking tea had Polish ancestry. The name “Varsho,” standing for “Warsaw,” was adopted for the new kitchenware – nickel silver, (brass with a high percentage of nickel), the alloy used to make kitchen vessels and cutlery, in general – even when the objects were produced by factories in Iran, as their origin goes back to the Norblin Silver-Plate Factory in Warsaw. Neda Razavipour’s packages contain examples of Varsho: a tin jar and a tray. There is also a crystal mirror, another Polish import (albeit the performer remarks that, unlike the prestigious Polish-plated objects, Polish crystal was considered to be inferior to the most desirable Czech products).

Tracking the alternative, parallel life stories of objects, let us bear in mind the repercussions of putting them to use. A chair, including a Polish one, was not just an artefact as such but also in a sense an instrument of western-style modernization. Its use entailed a change of social customs: the structure of the chair obliged one to sit on one’s own, rather than together with others, as was common with Persian furniture. They are simultaneously artefacts of modernization and anchors for our nostalgia; a nostalgia, however, for a future that never was, which, albeit lost, is – at the risk of sounding banal – one of the forces behind today’s nostalgia.

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Peformans "Podróżujące rzeczy". Neda Razavipour, 2015. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski

Razavipour’s narrative is founded on small history, ephemeral and powdery like dust or ash, and its anchors are the small tangible reality, the subject of everyday life, the elements of material culture. This work is not the artist’s first attempt to build bridges between Iran and Poland through art. In 2011, Slavs and Tatars presented their project The Friendship of Nations: Polish–Shi-ite Showbiz, in which they deliberately placed their search for the “alliance of the peripheries” in a conservative setting that lent itself to catchy narratives: Sarmatism, folklore, the sovereignty of nations, and revolutionary dates in the form of a fresco – vigorous and intentionally pop art – that covered centuries. Here, the accord is more discreet and inexplicit, expressed through the memory of objects and subtle notation of “movement memory”: dusting, cleaning, washing – gestures that reach directly into the cracks in existence.

I keep finding analogies with the incessant and futile busyness, so meticulously described by Brach-Czaina. At the end of her performance, Neda Razavipour wipes the assembled objects, and shapes the collected dust and fluff into what is called “koty” in Polish and “dust bunnies” in English; unfortunately, I don’t know what the Persian term is. It is as if she wanted to defy the ephemerality of the substance and tie it down. As for the travelling pieces, painstakingly wiped – so perhaps they have finally become well known – they have returned to square one and will now stay in Warsaw for good.

Translated from Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Olga Drenda is an ethnographer/anthropologist, author, and translator. She has published in 2+3 D, Slanted, Znak, Dwutygodnik, Nowy Obywatel et al., and has collaborated with Unsound Festival, Centre for the Meeting of Cultures in Lublin, and many others. She is the author of the Duchologia Polska page (facebook.com/duchologia) and the books Duchologia polska. Rzeczy i ludzie w latach transformacji (Karakter 2016), Czyje jest nasze życie (together with Bartłomiej Dobroczyński, Znak, 2017). Her interests include the anthropology of daily life, the transformation era in Poland and Central-Eastern Europe, and the subcultures of amateur creatives and collectors. She lives in Mikołów.

* Cover photo: Travelling pieces, performance, Neda Razavipour, 2015. Photo: Bartosz Górka, (c) U-jazdowski