Screening until: 15 June 2018

The film HASHTI Tehran portrays the peripheral spaces between urbanity and suburbia just outside the city of Tehran. Daniel Kötter opens up four different spaces of transition on the outskirts and shows parts of Iran that are rarely seen. The slow-paced pans of the camera across the buildings and landscapes are accentuated by conversations between real estate agents and clients, or people living in the area who talk about expulsion and migration. HASHTI Tehran tells the story of how social spaces are not created due to their centricity, but through the use of and occupation by people.

Hashti, in most traditional houses in Iran, is an octagonal space of distribution and circulation to direct the person towards the various parts of the house, the private (andarouni), and semi-public (birouni) are reserved for receiving people from outside and access to service areas.

Hashti, in most traditional houses in Iran, is the space behind the sar-dar (doorway). Hashtis are designed in many different shapes, including octagonal, hexagonal, square, and rectangular.

The hashti is a space of distribution and circulation. Hasht, which means eight, is an allusion to an octagon with several directions which makes it possible to direct the person towards the various parts of the house, the andaruni, or the birouni, towards the court or other dependences, according to the goal and the reasons of the visit.

Initially, the hashti was intended to regulate access and circulation. The private (andarouni) and semi-public (birouni) are reserved for receiving people from outside and access to service areas.

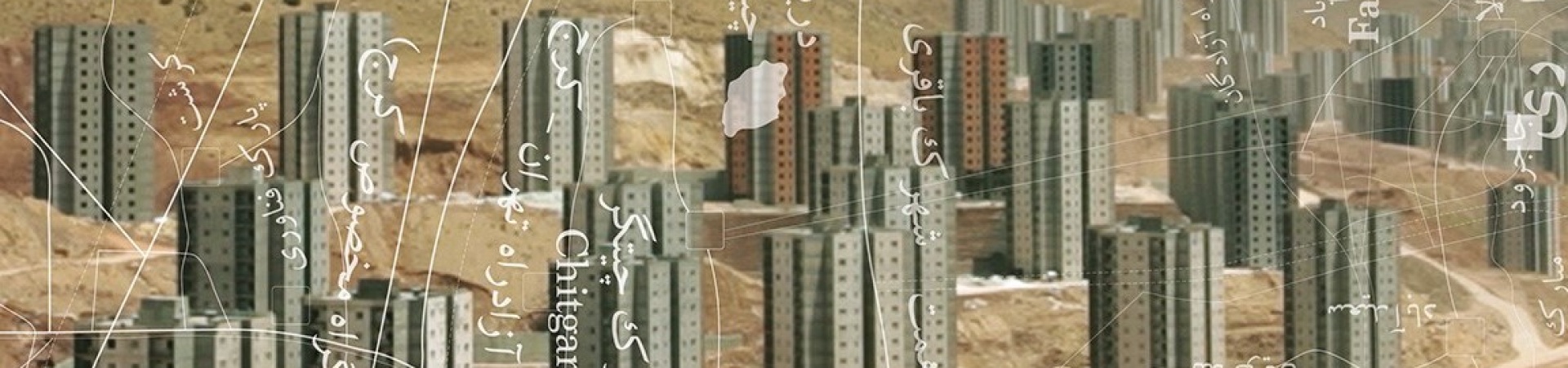

Based on the idea that Tehran itself represents a house, so to speak the inner circle of The Islamic Republic of Iran, the outskirts of the city become a space of transition between inside and outside, between urban and non-urban. Thus the film and discursive project HASHTI Tehran looks at four very different areas in the outskirts of Tehran: the mountain of Tochal in the north, the area around the artificial lake Chitgar in the west, the construction of social housing called Pardis Town in the far east, and the neighborhood Nafar Abad at the southern edges of the city. By combining a road-trip movie and architectural documentary, and by inverting the techniques of interior and exterior shots, the film HASHTI Tehran portrays Tehran through its peripheral spaces.

Film

cast: Sara Reyhani, Ramash Imanifard, Alireza Labeshka, Amoo Abbas

crew: Daniel Kötter (director, producer, script, camera, editing), Marcin Lenarczyk (sound design), Hedieh Ahmadi (sound recordings), Nafiseh Fathollazadeh (translations), Armin Maleki (translations), Somayeh Rezaei (translations), Alireza Labeshka (production manager), Sadra Keyhani (producer)

Daniel Koetter

Background

“Segregation” and “privatization,” “security,” and “control” are core terms of urban transformation in the developing cities of the 21st century around the globe. Its contested counterparts are “public” or “open space,” “access,” and “citizenship.” All these concepts seem stuck in the negotiation between an aspiration towards new liberal economies trying to connect to a global construction, and a business boom on the one hand and a tendency towards the preservation of a shared public sphere for all groups of society within the urban area on the other. HASHTI tries to shift this focus to areas where the controlling force of urban development seems to lose its influence, where definitions become blurry and fluid: the edges and peripheries, those contact zones, where city and landscape, nature and construction meet. Can a citizen who leaves the city for recreational or other purposes, still be called a citizen? Which societal function does he take on, which political role does he play in the moment where he enters or lives in the periphery of a city?

Administrative as well as geographical city borders divide space into inside and outside, into what belongs and what is beyond. The relation of those spaces on both sides of the border is therefore not symmetrical. The definitional authority is on the side of the city. The city would always determine the use and formation of space beyond its limits in a stronger way than the countryside would determine the urban space. One of the reasons for this is the fact that the city produces things, that it has to exclude from its center, in order to guarantee the functionality of living together: waste, dead corpses, criminals, and the socially marginalized. The space beyond the city limits therefore is predetermined for storage, settlement, and disposal of what is socially peripheral. On the other hand, the space beyond the boundaries of the city calls for this need for the city’s opposite: recreation, life in green spaces, better air, less density, and pollution. Living in the periphery therefore can be understood equally as both a stigma and a privilege.

The Tehran Case Study

Tehran’s peripheral geography shows a significant structural analogy with its social, environmental, and psychological divisions: the northern periphery, reserved for the upper class in penthouse apartments and for recreation in the “clean air” of the mountains, heavily contradicts the situation at the southern periphery, where smog and desert define the social life of the middle and low classes. While the geographical layout of the city with the mountains in the north and the desert in the south define a north-south axis, growth and development of the city are only possible on a west-east axis.

HASHTI as a discursive project in collaboration with Shadnaz Azizi, Kaveh Rashidzadeh, Amir Tehrani, and Pouya Sepehr and explored in four printed booklets, examines the different strategies of urban planners, architects, and sociologists in these areas. How is traffic, how are meeting places, contact zones, and gardening controlled and defined? And how do these spaces relate to the definition of interior spaces, the living room as a main forum in a society that regulates public space?

NORTH (TOCHAL)

In the north of the city lies Alborz mountain, reaching up to 5600m with its highest peak Damavand. It is the main water reservoir for the entire city. Alborz is not only used by tourists for hiking and skiing but also by Tehranis as an area for urban recreation. The northern city limits directly border the area of Tochal mountain, whose peak is connected with the urban area through a 12km long funicular. A mountain area used by urban people as part of their urban life.

WEST (CHITGAR)

In the west of the city, north of Chitgar Park, the city limits currently extend again towards the foot of Alborz mountain with a complex of residential high-rise buildings. While the structures themselves provide housing for middle-class families, the spaces “in-between” are renaturated for recreational purposes, including the artificial so-called Lake for the Martyrs of the Persian Gulf. A “second nature” is conceived, built, and offered.

Concrete structures, open-air pavements, and boat cruises inaugurate a specifically cultural form of visibility, meeting, and exchange, while “real nature” is taking over: endemic birds started to settle and environmentalists, biologists and urban planners struggle with algae and mosquitoes. How much “nature” serves the purpose of a specific outer-urban residential middle-class lifestyle?

EAST (PARDIS TOWN)

The social housing estate Pardis Town was built under the Ahmadinedschad administration 30 minutes by car east of Tehran. Cheap housing was constructed in 11 phases in the hilly and dry landscape. Neither shopping facilities nor schools nor public transport were provided in the beginning. Here the question is turned upside down: How much “city” is necessary to serve the basic daily needs of ten of thousands of working-class people starting a new life in an empty landscape?

SOUTH (NAFAR ABAD)

In Nafar Abad, the relation between residential space and open space is designed differently: while the municipality demolishes the neighborhood piecemeal to make way for the expanding needs of the adjacent Shrine, an important site for shia pilgrimage, the population temporarily inhabits the space in between the small-scale residential buildings by setting up furniture, armchairs, and chairs for local meetings, creating a subversive public version of the private living room.

Furthermore, the neighborhood is the location for the industrial treatment of wastewater from the entire city: the Tehran Wastewater Treatment Plant is situated in the vicinity. This is where the water, collected from Tochal Mountain and consumed by millions of Tehranis on its way through the city, ends up. In the south of the city, in districts like Shah-er-rey, the city boundaries reach towards the desert and the landscape gives a first insight of what will await those who will leave the city southbound: the gigantic and vast salt lake Namak, which contrary to Lake Chitgar, is a natural lake but does not provide water or opportunities for leisure activities.

BIO

Daniel Kötter is a filmmaker and music theater director whose work oscillates deliberately between different media and institutional contexts, combining techniques of structuralist film with documentary elements and experimental music theater. He has a strong interest in questions of urbanization in Africa and the Middle East.

His music theatre performances in collaboration with composer Hannes Seidl have been shown at numerous international festivals since 2008. Between 2013 and 2016, they developed the trilogy Ökonomien des Handelns: KREDIT, RECHT, LIEBE and they are currently working on a new trilogy called Stadt Land Fluss.

Kötter's series of films, performative and discursive work on urban and socio-political conditions of theater architecture and urban performativity was under development between 2009 and 2015 under the title state-theatre Lagos/Teheran/Berlin/Detroit/Beirut/Mönchengladbach (with Constanze Fischbeck).

His film and text work KATALOG was shot in twelve countries around the Mediterranean Sea portraying sites and practices related to the definition of the public sphere. It was presented at the Venice Biennale for Architecture 2014.

Between 2014–17, he was working with curator Jochen Becker (metroZones) on the research, exhibition, and film project CHINAFRIKA. Under Construction.

His documentary Hashti Tehran premiered 2017 at the expanded Berlinale Forum and won the special the German Short Film Award.

http://www.danielkoetter.de/projekte/hashti-tehran

* Cover photo: HASHTI Tehran poster (fragment)