Let us start by pointing out that no place is given to us for keeps. Including those that some of us are privileged to call a home, while many people in the world have been forced to leave theirs behind. Despite the fact that humankind has been doing its utmost to dominate and appropriate the planet, it is no more than just a guest on this planet, the only one with which it is directly familiar. . We share the planet Earth with over 7.7 billion people and 1 or 2 million animal species. Considering that fungi have existed on our planet for at least a billion years, humankind is, in a sense, the Johnny-come-lately – and it was precisely the symbiosis of fungi with plants that was one of the engines that powered evolution, paving the way for our own world. If we accept it in its entirety as a common asset, co-hospitality becomes the obvious stance. It is the case, however, that today – as Zygmunt Bauman pointed out – it is the social and class divisions and humiliations characteristic of a culture based on ownership and market forces that are considered natural facts,1 whereas the fact that we are all the children of mother nature is disregarded. “It is also impossible to practice a universal coexistence in a culture constructed without respect for our natural belonging,” pointed out Luce Irigaray, 2 and Zygmunt Bauman echoed Kant: “Nature commands us to view (reciprocal) hospitality as the supreme precept we need to – and eventually will have to – embrace and obey in order to bring to an end the long chain of trails and errors, the catastrophes the errors cause and the devastations the catastrophes leave in their wake.”3 The paradox of hospitality rests in the fact that it is a positive value but it cannot be imposed on anyone; it must stem from the individual’s own inner need. “Feel at home,” urges the host. But who can point to the boundary between feeling at home to an acceptable degree and feeling “too much at home”. Between these two states there lies a problematic and nebulous area.

Viewing our planet as the shared home of all creatures, animate and inanimate nature, we note that our species, albeit a relative newcomer, has behaved in an exceptionally cavalier way, and rooted in our experience is a profound hierarchy of unequally distributed privileges. Within the species, some groups have usurped the right to decide who should be welcome as a guest and where, who should be given shelter – and only, at that, to an extent that this does not in any way impinge on the principles imposed by these groups. This is, at best, conditional hospitality.4

Hospitality is – to follow a dictionary definition – the “cordial and generous reception of a guest.” Hospitality involves “forsaking hostility – both on the part of the local host, and the incomer, a stranger.”5 Hospitality requires an understanding of the ethical and moral imperative, practicing coexistence and incessant questioning of one’s own privilege.6 Hospitality is something more than inviting a dear friend for tea at a time convenient to us. It involves two parties – the guest and the host. It is easy to play host to someone that shares our own way, but more difficult when it comes to someone who behaves differently. “Genuine hospitality cannot be assimilation,”7 since it is only possible to play host to that which is different.8 Hospitality begins with granting someone a say, a place and support – and not necessarily in circumstances that are the most favorable for us. To offer someone a demarcated space, in which they can integrate with us, accepting our rules and the limits of integration is not hospitality. It must mean opening up to the needs of the other, who may want to occupy a different space from the one that we have allocated to them. To welcome a visitor is to be open to everything that may come with their arrival; this may be something unexpected, or not something that we had hoped for, thus “before feeding or sheltering the other, it is important to ask him or her what they expect from us.”9 The relationship between the host and guest is delicate and fragile and demands to be breached.

Seminarium Re-Directing: East 2016 na Kocu Dydony projektu Małgorzaty Kuciewicz i Simone de Iacobis. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Residencies versus Hospitality

I have been one of those involved in creating the residential program in Ujazdowski Castle almost from its launch in 2003, but nobody gave me a manual at the outset on “residential hospitality”, so you could say that my point of departure was ignorance and a willingness to learn. If we assume, however, that “not knowing” is a condition of hospitality, that was precisely the appropriate starting point to attempt to put it into practice. I have achieved my understanding of how to curate residencies through action. As it turned out, this is a practice that is completely different from organizing exhibitions or running projects; the key is interpersonal relationships and dialog, as well as the readiness to share in the participation of achieving a creative space in which all the people involved coexist, and negotiate their positions.

In due course I came to understand that the practice of empathy, care, gratitude, mutual respect and consideration as well as quite a lot of invisible work put in are what fuels the kind of residency that I would like to manage. At the same time, I came to acquiesce in the fact that the lack of representation for these practices is the daily fare of residency curators. Further problems that require urgent reflection and solution include: who can we welcome as guests and why; where and how the funds are obtained; and what hierarchies, restrictions and exclusions hide behind such choices. It is also a must to revise the models of residential programs so as to make them more inclusive, equal, feminist and ecologically responsible.

In an institution, the “residential hospitality” may be packed in a systemic procedure. Each organization works out their own “hospitality rider”.10 It is quite obvious that in such a setup, the resident plays the part of the guest, and the institution – the host. In practice, the relationship is more nuanced, evading simplistic pigeonholing and definitions, immersed as it is in the daily mundanity, with all its pragmatic, affective and metaphysical surprises. Did you do your best? Ask this question of a resident who felt insecure because it had not occurred to you to collect her from the airport. With each new guest, we learn how to practice hospitality.

The very fact that we move production to the backburner, focusing instead on the process, creates a less-than-clearly-defined space in which both the organizers and guests lay themselves open to surprises.

The successive generations of residents have been the ones to teach me hospitality and I am indebted to them all. Today it is Obieg that is my host and provided for me the space to have my say in talking about things that remain invisible, but which are my own experiences. Out of the many, I have chosen a few episodes that remain my source of inspiration.

Arie. Zdjęcie: Krzysztof Łukomski.

Arie

In 2017, while working on the exhibition-meeting titled Gotong Royong: Things We Do Together, we had as guests many fantastic people. At some point we became aware that two women residents from Brazil were complaining of a presence in the Castle studio, where they were staying. Luckily, in our temporary collective Intervalo Escola – Time for a Break, which came together for the occasion of the exhibition, there was a young artist who was experienced in negotiations with beings that exist outside of our notion of materiality. With the help of methods that only he knew but that involved sage, he made contact with the spirits and the presence ceased to oppress the women. They no longer experienced night-time episodes of pressure on their chest (“as if someone is sitting on me”), the sudden, inexplicable slamming of doors and windows or objects falling down of their own volition. A few weeks later, guests from Indonesia came to stay in the same studios. During a winter walk, Arie asked with a smile, “Do you know, Marianna, that we are living with spirits?”

This was obvious for me, so, concerned, I asked, “Yes, I do know. Is everything all right?”

“Yes,” said Arie. “A few days ago I was lying on my bed, looking at the table a few meters away, and suddenly – wham! The speakers that were standing on the table crashed to the ground. I knew what that meant. I made my introduction out loud, speaking in Indonesian. I said that I was just a temporary visitor and that I respected the presence of the Spirit. I asked it not to haunt me. We sometimes see a kind of shadow out of the corner of our eye, but things don’t fall down any more.”

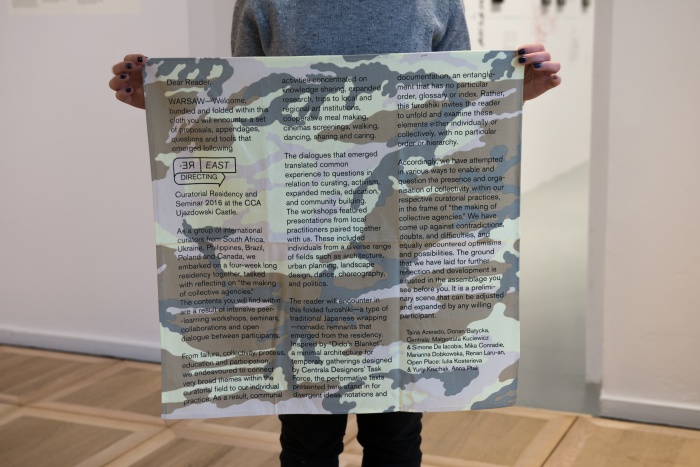

RDE 2016, Furoshiki. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Love Letters

During this year’s seminar Re-Directing: East 2019, Aziza Harmel told us about her practice of writing love letters from one institution to another – what a great way to communicate! In 2016 together with the men and women taking part in the seminar RDE 2016, we edited the object–publication; the shape of its cover was in its form related to furoshiki – a Japanese cloth used for packing and carrying objects of various sizes. Inside the piece of cloth, tied into a bundle, there are messages and tools for future users – in particular, future residents. Using shared learning as the point of departure, Tainá Azeredo drew a diagram of the relationships that came into being during the seminar. Dorian Batycka described the political situation in Poland and the actions he had carried out with a group of friends outside the Frontex building and in the Warsaw Uprising Museum. Małgorzata Kuciewicz and Simone de Iacobis handed over the instructions of how to make Dido’s Blanket, a “temporary architecture for meetings,”11 which accompanied us during the seminar and which to this day we still have in storage for our program. Renan Laru-an created a conceptual object/puzzle, and Mika Conradie philosophical puzzles. As for me, I shared a simple exercise for tuning into listening in a group. The gesture of hospitality consisted of an attempt to describe the space in which the future guests would be arriving, and welcoming the visitors that the authors would not be entertaining themselves. Our furoshiki is a love letter sent into a non-defined future to unspecified recipients.

Juliette Delventhal, Paweł Kruk, Piec, 2011. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Juliette

Juliette Delventhal was our first chef-in-residence. She taught me the conviction that shared preparation of food and communal eating are a precious meeting space. Even before arriving for her residency, she wrote, “I believe that my own cooking will be profoundly altered by this experience. I have had the privilege of traveling to many places and each of them, together with the local flavors, made a deep impact on my cooking. I am really looking forward to the opportunity to be able to prepare meals and eat them together with the community gathered in Ujazdowski Castle. I would like to fulfil my dream of a big, long table shaded by trees and being able to build and use a simple field kitchen in the open air.” During her residency, we battled together against institutional and procedural barriers to make her dreams come true. We found a master potter, and succeeded in negotiating the right space with the institution, which was hidden from the view of Castle visitors behind an ugly tin fence, on what was at the time a messy construction site. A few weeks of preparation later, a table was erected under the trees, as well as a superb, massive bread oven – a little comical in its shape, but it functioned perfectly. Juliette was the caring hostess of many an unforgettable evening, teaching us how to produce the best possible dough for pizza. But above all she created a space in which that activity can continue. The oven is a pretext, inviting participation with its physical presence. Shared meals, cooking and evenings spent in that space have become a staple of our residential program.

Ambra Pittoni i Juliette Delventhal, Kolacja Ocalonej Nocy [Saved Night Dinner], 2012. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Silent Supper

Dear Marianna

You are invited to

Saved Night Dinner

In order to attend the celebration you will have to know some rules.

We kindly ask you to carefully read the following instructions

RSVP

Dress code: elegant as if you were celebrating the end or the beginning of something important.

The dinner will take place in silence. Please remain silent from the moment that you enter the dinner space until we declare the end of the silence.

The silence will last long.

When the silence ends, a strong drink will be served and each person will be invited to make a toast. Think about what you would like to make a toast to on that night.

You are free to improvise, if you wish.

The dinner will take place on 16 August 2012 at 10 pm

in the courtyard of Ujazdowski Castle.

With Very Best Regards

Ambra Pittoni and Juliette Delventhal

All the Castle residents at the time and the residency program team members had such a printed invitation delivered to them in person. Despite having assisted Ambra and Juliette, I was not privy to the ins-and-outs of this mysterious event. A year after the stove was constructed, Juliette returned to Warsaw with her husband Paweł Kruk and her daughter Zoe, in order to set up a permaculture fruit-and-vegetable garden in front of the Laboratory where the residents were staying. By a stroke of luck, this coincided with Ambra Pittoni also staying as a resident; for years she had nurtured the dream of organizing a silent dinner in collaboration with a sensitive female chef.

At 10 pm sharp we met in front of the Castle, dressed to kill and excited. Even though we were quite meshed as a group, we all felt a bit on edge. I have no idea how long the meal lasted. It was excellent. To a great extent it was prepared with the produce of our garden. At first, the silence was uncomfortable, but later it felt more natural. Wine also helped us to relax. When in the end Ambra announced the end of silence, the toasts that gushed forth were the most tender words of mutual gratitude. The invitation had taken us by surprise – something that could have made some uneasy. But our hosts were not setting a trap – on the contrary, they conjured up a moment in which silence made words come into being and resonate. What got said that evening was important and meaningful. I shall never forget that night.

Oprowadzanie po wystawie Gotong Royong. Rzeczy, które robimy razem z perspektywy jej opiekunek, 11/01/2018. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Exhibition Hosts

“Marianka, now we will take you on a guided tour!” was what I was told one day by the guardians of the exhibition Gotong Royong: Things We Do Together, when I came to meet up with them. The exhibition had a rich public program with over a hundred events taking place. In the space of the exhibition where it was all action, and where we spent a lot of time with the artists and program participants, close links developed with the guardians. They were at all times hands-on, and often joined in the action. Nevertheless, their offer to give me a guided tour came as a surprise and I was truly moved by it. All of a sudden, by taking the initiative and volunteering as hosts of the space, they altered the relationship between the curator, institution and auxiliary workers who usually stayed in the shadows.

That day, they took me around my own exhibition in the most authentic and poignant way possible, transporting the narrative into the sphere of their personal experience and relationships with the works and practices represented, and I followed them behind, my eyes misting over. At the end of the tour I asked whether they would consider an action replay for the public. I was delighted when they said yes. This was how one of the most interesting and popular events of the public program came into being: host-guided tours: Anna Borowska, Ewa Kiełbus, Agnieszka Kłos, Jadwiga Kozera, Hanna Wcisło and Jadwiga Wolfman.

The House of the Collective

The Indonesians are incredibly hospitable, as I had an opportunity to experience for myself. Informal artistic collectives often start with inviting a group of friends home, and home is often an open space, also for strangers. There is an ongoing, endless nonkrong – the custom of idly hanging around, squatting and smoking together, and chatting so long that in the end there is nothing left but to stay the night. In our culture, to stay the night is an intimate act that shows a close relationship between host and guest – for Indonesian collectives, it is normal. This is how, for example, Jatiwangi Art Factory and the village of Jatisura or KUNCI in Yogyakarta operate. I very much like the vision of an art institution as an open house.

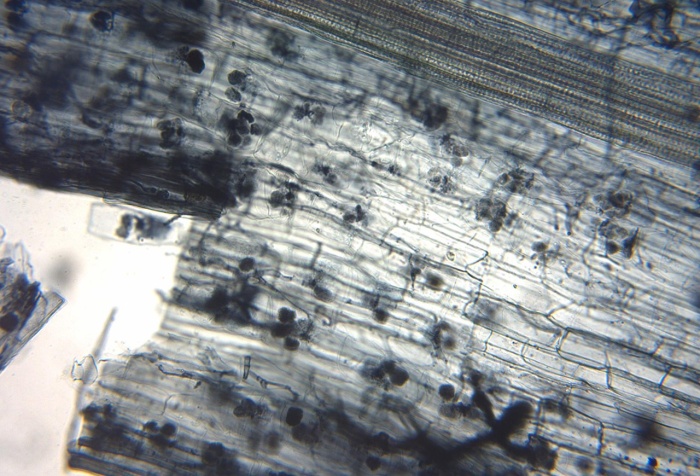

Mikoryza arbuskularna widziana pod mikroskopem. Komórki korowe korzenia lnu zawierające arbusklue. Źrodło: Wikimedia commons.

Radical Hospitality

To finish, let me get back to Zygmunt Bauman and his take on the philosopher from Königsberg: “(…) Kant observed that the planet we inhabit is a sphere, and thought through the consequences of that admittedly banal fact: as we all stay and move on the surface of that sphere, Kant observed, we have nowhere else to go and hence are bound to live forever in each other’s neighbourhood and company. Keeping a distance, let alone lengthening it, is in the long run out of question: moving round the spherical surface will end up shortening the distance one had tried to stretch.”12

No-one knows how much time we have left on this spherical planet of ours, but if we are to continue, it will be not only in the company of other people but certainly also in the proximity of fungi. Jacques Derrida stressed the necessity of unconditional, radical hospitality. Taking a closer look at fungi – our co-inhabitants on planet Earth – one can say that they pioneered radical hospitality. Mycorrhiza is a symbiotic association between certain fungi and plants. Plants host the fungi in their root system and share with them the products of photosynthesis, and the fungi in turn supply the host plants the microelements and mineral compounds from the soil. Mutual hosting is the underlying strategy that makes survival possible. The radical (from the Latin: radix – root) hospitality of the fungi towards humans begins with preparing the Earth for everything that is familiar to us today. When billions of years ago fungi began to colonize our planet, the first land fungi derived (mineral) nourishment from rocks, turning them into the soil that now feeds us.

Today, when nation states diligently guard their non-porous borders, while capitalism and other oppressive systems in which we have come to live are introducing yet more segregation and hierarchy, it is hard for us, ordinary people to practice planetary hospitality. An interspecies symbiosis could become the new face of radical hospitality, based on an unconditional economy of giving, under which we would agree to coexist on the planet in mutual respect of our differences, opposing capitalism.

When the world around us is mad keen on making us give up faith in hospitality, and interpersonal relationships appear powerless in the face of “big politics”, it is precisely the interhuman and interspecies mutual hospitality that can become the practice of everyday resistance. Only when we dare to activate it individually and collectively, will we be able to put real protest into practice.

Translated from Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Marianna Dobkowska – curator of residencies, projects and exhibitions. Publications designer and editor, production manager of new artistic works. Co-creator of the residential program at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw almost from the very beginning. She sees curatorial practice as a tool for building relations and creative situations based on long-term and often international collaboration, combining practices derived from the fields of the visual and performative arts, education and activism.

She has curated and co-curated projects including: Public AIR, We’re Like Gardens, Porthos : Marszewski at Marszałkowska 9/15, and Action PRL, carried out in public space and based on broad active participation by the general public. She is the co-author and co-curator of the international curatorial seminars Re-Directing: East (2013–). During her visits to Indonesia she researched socially and politically sensitive artistic practices and examined in depth the working methods of the art collectives on Java. Together with Krzysztof Łukomski she curated the two-year project Social Design for Social Living (2015–2016), presented as part of Biennale 2015 in Jakarta, the corollary of which was an exhibition of the same title in the Indonesian National Gallery in Jakarta and the exhibition-cum-get together Gotong Royong: Things We Do Together (2017-2018) in Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art. She is currently editing the post-reader of the project. Editor of the magazine The Residents, presenting the residents at Ujazdowski Castle. Since 2014, together with Arton Foundation, she has been working on the Jan Dobkowski archive.

Marianna Dobkowska Marianna Dobkowska graduated from the Warsaw University with an MA in art history, and a postgraduate curator’s degree from the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. She received two scholarships from the Minister of Culture and National Heritage (2012 “Young Poland”, 2016 – Minister’s scholarship); she holds CEC Artslink (New York) and Backers Foundation (Tokyo) scholarships.

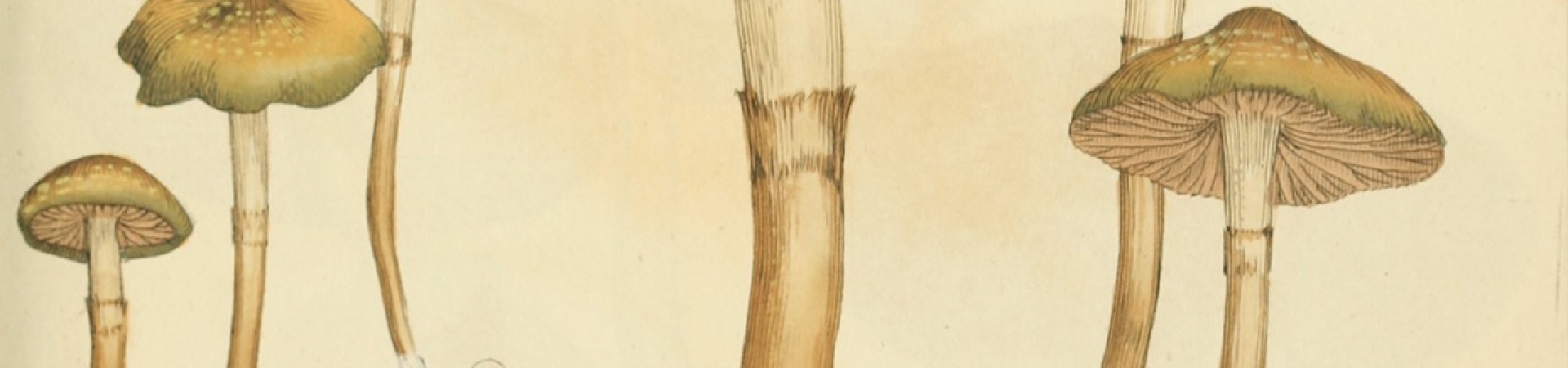

*Cover photo: an illustration of Cortinarius hinnuleus mushroom from "Coloured figures of English fungi or mushrooms" by James Sowerby (Archive.org), London, pronted by: J. Davis,1797-[1809]. Source: public domain, Wikimedia commons.

[1] Magdalena Środa, Zygmunt Bauman, pielgrzym w świecie turystów, in: “Gazeta Wyborcza”, Magazyn Świąteczny, 13 January 2017.

[2] Luce Irigaray, Toward Mutual Hospitality, in: The Conditions of Hospitality: Ethics, Politics, and Aesthetics on the Threshold of Possible, ed. Thomas Claviez, Fordham University Press, New York 2013, p. 43.

[3] Zygmunt Bauman, Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds, Polity Press, Cambridge, Malden, p 125.

[4] “In Derrida’s take, unconditional hospitality means the relinquishment of power, the suspension of the legal norms and the social contract that had guaranteed the dominant position to the host—that is, the state. In turn, conditional hospitality does not allow for welcoming each and every foreigner. Moreover, it necessitates a prior check on their legal status, thus turning the stranger into a quasi-enemy. The political dimension of the right to hospitality is directed against those who need it, and rather exposes the generosity of those who give it and the duties of those who receive it.” Krzysztof Loska, Gościnność warunkowa czy bezwarunkowa?,in: „Ethos” 28 (2015) no. 4 (112), p. 211.

[5] Cezary Wodziński, Odys gość. Esej o gościnności, Gdańsk 2015, p. 11.

[6] See Ewa Majewska, Gościnność, faszyzm, sfera publiczna. Kontrpubliczności podporządkowanych innych, in: “Opcje”, http://opcje.net.pl/ewa-mejewska-goscinnosc/, [accessed 12 September 2019].

[7] Łukasz Moll, W gościnie, czyli tam, gdzie granice docierają do swych granic,, in: “Opcje” no 3 (104) 2016, p. 56.

[8] Op. cit.

[9] Luce Irigaray, Toward Mutual Hospitality, op. cit., p. 9.

[10] Hospitality rider is a list of requests for the comfort of the artist on the day of the show, commonly practiced in the world of the theatre, performance and music.

[11] This is how the artists themselves referred to it.

[12] Zygmunt Bauman, op. cit., p. 125.