The intricate ties between the early communist government and the Russian avant-garde are well-documented. These relationships flourished in the 1920s with many forward-looking artists willing to lend the government a hand in establishing the new aesthetic regime. For a while, the leaders were repaying in kind, elevating the few selected artists, while making use of visual arts in the ongoing radical transformations. Less known is the fact that many of these techniques were pioneered before, during a short yet electric tenure of the Provisional Government, and its liberal-populist leader Alexander Kerensky. The one individual overseeing cultural policies was Mikhail Tereshchenko, the “first Ukrainian oligarch” and a patron of the arts. One century since, Ukraine is still a country where magnates of industry are a historical force of their own. The following text is the transcript of a didactic installation1 located in PinchukArtCentre, an art institution named after the eponymous philanthropist.

The February Revolution of 1917. It was as rapid and premature as it was completely inexplicable. The revolt was elemental, and nobody in particular could claim the role of its instigator. Planned palace coups remained in the dreams of the conspirators, and party leaflets calling for regime change did not come out from the printing presses until after the fact. The events exceeded the most daring expectations, inspiring bewilderment and awe. The giant of autocracy shuddered and fell. Why? Attempts to find the single reason for the Revolution are futile. Military defeats that embarrassed the army, overpopulated agrarian regions, food shortages, the scheming opposition, the anti-German frenzy and the real influence of Prussian agents had all played a role. Curious minds can rest in the knowledge that every single one of these reasons would have sufficed. And yet, history favors the daring: those who can make the most of the turmoil without getting bogged down in second-guessing the rationale behind the events.

In 1917, the people who fit this description were aplenty. The opposition in the State Duma, the moderate circle of the industrial elites, discontent with czarist policies, proved to be one of the most enterprising groups. It was certain that, after the unorganized masses complete the revolutionary act, other people with more political experience would have to make sense of the new order. Moreover, why await the approval from the crowd if you can empower yourself? The new authority, with the conciliatory title of the Provisional Government, was established in order to “prevent anarchy and restore public order.” As will become apparent later, the key roles were appointed long before the revolution. The dawn of March 2 brought unexpected news: 11 people were announced as members of the parliament that would lead the country towards a renaissance and victory in the war. At one early session in the Tauride Palace, a voice from the hall filled with worried people yelled, “Who elected you?” The answer was, “We were elected by the revolution!” Who were these people brought to the top by the wave of protests? It was a homogenous group of intelligentsia, merchants and industrialists, familiar to all readers of liberal newspapers. All but two appointments came as no surprise.

Alexander Kerensky was a socialist, a revolutionary, and a fiery orator. Nobody could rival him in the art of capturing the mood of the masses. In his military-style trench coat, he looked like a meaningless figurehead of the people’s revolution in the capitalist government. The role seemed not to have worried Kerensky overmuch. He acted as if the February Revolution was his doing, and even if he was not the one to have caused it, he sure could stand at its helm. Mikhail Tereshchenko was his polar opposite. Despite his seeming modesty and impeccable manners, this young progeny of a Ukrainian sugar refiners’ dynasty was one of the richest industrialists in the empire. And yet, Tereshchenko was known primarily as a patron and connoisseur of arts. Before the revolution, he tended to stay out of public politics, occasionally financing opposition parties and scheming about overturning the outdated autocracy in elite political salons. He contributed to the meteoric rise of his friend Kerensky and backed his candidature for the position of the leader of the Provisional Government with his sugar resources. Without exaggeration, it was his revolution as well.

During its short yet eventful rule, the Provisional Government managed to demonstrate both blatant dilettantism and great cunning. We will touch on two details: the new government’s overweening desire to continue the old war, and its relationship to art. The Provisional Government began by voicing its desire to continue the war “till final victory,” and to fulfill the czarist commitments to the allies. And yet, the society was progressively more exhausted by the war, and desertion became ever more widespread. In an attempt to boost the morale and restore discipline, the freshly minted Minister of War Kerensky visited the frontline. His posture and habit of addressing the soldiers as his equals hinted at the popular upheaval in the capital. Exhausted soldiers welcomed their new charismatic commander and seemed ready to reenter the heat of battle. And yet, enthusiasm is not enough for a successful military advance.

The state did not have the resources to equip the army, and the hopes of quick credits from western allies proved futile. By the third day of the Provisional Government’s rule, Tereshchenko as the Minister of Finance raised the question of internal loans: the citizens were to foot the bill for the state’s revival. The populace could buy state bonds, receiving 5% interest over the following years. Keenly aware of the spreading anti-militarist mood, he did not mention the war in any of the accompanying documents, describing his idea as the “freedom loan” instead. The contradiction inherent in the phrasing did not deter him. The inspired title was to be evocative of liberation and building the republic based on the principles of equality and brotherhood. Advertising the loan became first a passion, and subsequently the only task of the young magnate. He met with bankers, economists, public activists, and opinion-makers every day. His efforts were not in vain: they produced an inventive promotional campaign. “The Committee for the Encouragement of State Loans” established by Tereshchenko released appeals, leaflets, and gramophone records, and even screened cinematographic plays celebrating the loan of great hopes. He also developed a system of material incentives, relying on the reputation of his friend, “the people’s minister” Alexander Kerensky.

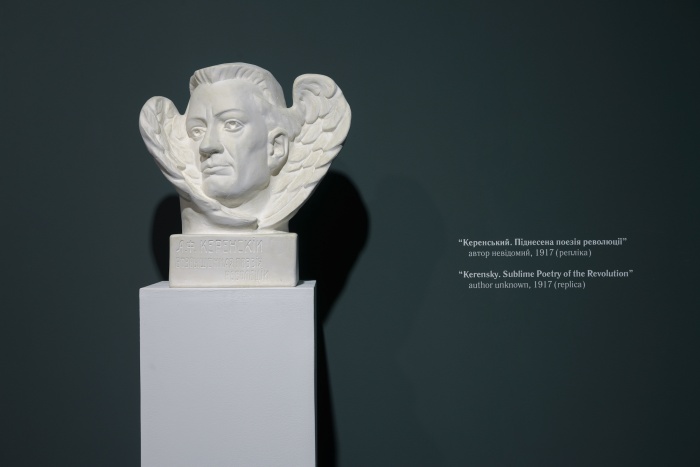

The government gave each citizen who bought several thousand roubles’ worth of bonds a plaster bust of Kerensky as the poet of the revolution. The offer caused a frenzy, and there was soon a shortage of laurel-wreathed heads of the people’s minister. Those who did not receive one had a choice of more modest revolutionary memorabilia, including medals, postcards, or posters glorifying freedom, equality, and Kerensky. In the spring of 1917, this hastily put together assortment did not yet seem too shabby. The politically engaged public was happy to pay for an opportunity to see their idols, buying up tickets to concerts which starred the heroes of the revolution. Enterprising businessmen, political parties, public organizations and, last but not least, the Government itself seized the opportunity to line their pockets and promulgate their agenda. The production and consumption of revolutionary images reached industrial scope.

Larion Łozowoj, Beetroot Revolution (fragment instalacji), 2018. Fotografie dostarczone przez PinchukArtCentre © 2018. Fotografia: Maksym Biełusow.

Larion Łozowoj, Beetroot Revolution (fragment instalacji), 2018. Fotografie dostarczone przez PinchukArtCentre © 2018. Fotografia: Maksym Biełusow.

Larion Łozowoj, Beetroot Revolution (fragment instalacji), 2018. Fotografie dostarczone przez PinchukArtCentre © 2018. Fotografia: Maksym Biełusow.

At the same time, the image of the “main revolutionary” took on a life of its own, departing ever further from the insomnia-addled real person by the name of Alexander Kerensky. Newspapers were generous with inventive epithets, describing him as “a friend of humankind,” “the genius of freedom,” or “the sun of the free country.” Kerensky found getting about on foot increasingly hard: agitated crowds carried “the poet of the revolution” from his car to a podium. The image of the leader uniting revolutionary acts with creative actions was as appealing to intelligentsia as it was to the masses. Kerensky gained public trust due to his origins and friendships with various intelligentsia circles. The futurist Velimir Khlebnikov included Kerensky in the board of directors of his imaginary organization, “The Society of Leaders of Planet Earth,” as the leader of the planetary supra-state (along with avant-garde artists, poets, and composers from around the globe). And yet, the image of the revolutionary artist was appropriated by the perfectly real government that auctioned Kerensky’s portraits signed by the revolutionary leader himself.

Meanwhile, the art sphere was undergoing a deep crisis. The system of support and patronage to which many artists owed their livelihood crashed. Rapid inflation and the fear of popular retribution encouraged the elites to seek refuge in emigration. Their fortunes, numbering in the millions, flowed abroad, leaving artists to fend for themselves in new unpredictable circumstances. And yet, the art milieu gladly welcomed the triumph of democracy. Enamored with the revolution, artists promulgated republican ideas with their pencils and brushes, helping the masses to express their creative energy. Tasked with propaganda, art took to the streets. Exhibition halls and salons emptied out. Artists were confronted with an unprecedentedly broad canvas, encompassing posters and illustrations, simplistic political sketches and caricatures, designs for speech-stands and public manifestations, and, last but not least, propaganda materials for the entire spectrum of political forces, old and new. The Constitutional Democratic Party, the Socialist Revolutionary Party, the Bolsheviks, and the Mensheviks vied for the sympathy and know-how of the art milieu, offering their own terms.

There was also a formerly unknown, yet particularly generous and inventive force at work. The Provisional Government itself had all sorts of incentives at its disposal, including state commissions and individual support schemes for loyal artists. Many artists welcomed the emergence of the new player. Newfound independence from the whims of patrons brought them great joy and ethical relief; now they could rely on those they were happy to serve: the public and its elected representatives. Many came to trust the initiatives of the Provisional Government with its freethinking and charismatic leaders. The authorities’ aesthetic ambitions grew, as did the need to prevent public resistance to increasingly unpopular steps. “The enemy invaded our country and is threatening to bring back the old, now dead regime,” stated one of its first proclamations. The government tried to persuade the population that the war would have to be waged until the final victory through a targeted art campaign. Journals brimmed with commissioned militaristic drawings illustrating the massacres perpetrated by the enemy, the heroic soldiers, and anecdotes from the frontline. The front pages of most newspapers contained calls to donate to the army and to acquire state obligations.

One event provides particularly telling proof of Minister Tereshchenko’s interest in the art trappings of the loan, his ideological brainchild. On May 25, the capital saw a celebratory demonstration joined by organized art communities. Few descriptions of this solemn affair survive, and yet, all maintain that the event was not merely an advertising campaign for the loan: it was to lay the groundwork for a new national celebration. “The Freedom Day,” as the organizers had christened it, was to become a day of rest from post-revolutionary hardships, doubts, and sorrows. Concerted efforts of hundreds of artists were to cure the public of these ailments, at least for a time. This explains why the Freedom Day was also dubbed the Artist Day, marked by the first organized appearance of art unions, and celebration of creativity freed from censorship and autocracy.

The procession was supposed to symbolically unite two points on the city map, the Academy of Arts and the Tauride Palace as the seat of government. As the column set off, the trucks lavishly decorated with posters, wreaths, and flowers started to flash their lights. All colors of the rainbow replaced the familiar black and red hues. Traditional official announcements and well-orchestrated festivities were replaced by impromptu speeches of the artists and agitated shouts from the public. The piebald procession remained in the memories of city residents for years. Actors played out tableaux vivant and scenes from the war and revolution. Dozens of cars and cabs with culture officials filled neighboring streets, celebrating the spring, freedom, and the national loan. In the afternoon, all columns joined up and solemnly marched past the government palace towards the concluding meeting and concert. The celebration seemed to have been a success.

But look, what’s that commotion? One car disrupts the ceremony, breaks out of the column, and rushes towards its front. A drab and grimy truck had only a black flag with a skull and bones for decoration, signed “317 Heads of the Planet Earth.” The truck carried a small group of artists who disagreed with the military ambitions of the Provisional Government. The artists intent on undermining the celebration plowed into the thicket of militarist proclamations. The truck became the battle vehicle for the organization of “futurians.”2 The vehicle seemed to mock the procession, the sunny day, and the crowd’s solemn mood. Its sides were hastily plastered with sheets of paper covered with anti-war slogans in black ink. The open platform bore a comic display of the leaders of the globe, with Vladimir Mayakovsky and Velimir Khlebnikov reciting rhythmic manifestos at the helm.

"We alone have rolled up your three years of war into a single spiral, a terrifying trumpet, and now we sing and shout, we sing and shout, drunk with the audacity of this truth: the Government of Planet Earth already exists. We are It.”

Khlebnikov recited what was to become a part of his poem “War in a Mousetrap,” “Yesterday I whispered: ‘Coo! Coo! Coo!’ And flocks of wars flew down to peck the grain from my hands.”3 Rich in the zaum (“beyond sense”) symbolism, the poem was radically dissimilar from humanist requiems published in literary magazines of the time by the thousands. In order to fully appreciate the antiwar pathos, the reader had to be deeply aware of the great futurist’s thinking at the time. But let us not underestimate the public’s capacity for listening and hearing. Moreover, the public would get a chance to read the work under less charged circumstances: it was published in a government newspaper In the Name of Freedom, advertising the national loan. The press made particular note of the fact that most art communities, even Cubists and Futurists as the most progressive branches, took part in the celebration. It also rejoiced in long lines to kiosks: loan obligations were in high demand.

Over the course of the following months, Tereshchenko’s advertising campaign continued unwaveringly across the country. Despite continuous tumult, the growing number of citizens signed up for the loan, and the number of subscribers reached a million by autumn. The colossal funds raised by the government allowed the war to continue and enabled the mounting of a large-scale offensive on the frontline. But let us not judge the artists that dared to risk their freedom for the higher goal, borrowing paper, ink, and a government-issued vehicle for that purpose, too harshly. “Are we wrong in assuming that the war monstrosity has but one eye, and all we need is to hide in sheep’s clothing, sharpen a stick and blind it?”4 they asked themselves before the memorable event. Indeed, were they under any obligation to make their poetry less caustic and more publicly accessible? Should they have foreseen that the futurist attempts to rile up the public would be futile? After all, the public had been facing prolonged provocations of the war, this chief futurist, who paced the world in a bloodied mantle of endless dusk. The public was also lulled by the spectacle orchestrated by the government, which turned out to be more inventive than any artist could hope to be.

Translated from Ukrainian by Iaroslava Strikha

BIO

Larion Lozovoy is an artist and researcher based in Kyiv. He focuses on economic history of Central-Eastern Europe, ideologies of modernization and creativity. He graduated from the National University of “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy” in Ukraine, with degrees in Philosophy and Political Science. He completed the Course of contemporary art at the Kyiv School of Visual Communication, Moscow Curatorial School by V-A-C Foundation and WHW Akademija (Zagreb, Croatia). He authored critical texts for Korydor, Prostory and Krytyka Polityczna online magazines. Additionally, he engages in publishing works in contemporary European philosophy and public policy analysis.

*Cover photo: A still from Kerensky Rising, author’s montage based on archival footage, 2018. A part of the Beetroot Revolution by Larion Lozovoy.

[1] Beetroot Revolution by Larion Lozovoy within the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2018.

[2] budetliane in Russian.

[3] Collected Works of Velimir Khlebnikov. Vol 3: Prose, Plays, and Supersagas, translated by Paul Schmidt, Harvard University Press, 1989.

[4] “October on the Neva,” ibid.