“From time to time, stop to think about what you are about to do, and then try to do the opposite”

(Cesare Pietroiusti, Non-functional thoughts, 1987-2015)

If I had to imagine someone being busy-idle, it would be Goncharev’s bedridden character, Oblomov. This good-for-nothing man would give the impression of being idle in a new and unusual place for him, such as the kitchen, busily doing nothing much at all. I can picture him roaming for recipes that he would never learn how to use in his non-practical life as a slothful nobleman of 19th century Russia. And where can one find all the Oblomovs of today?

Maybe they practice their social influence by simulating action and appearing to be hyperproductive in a society that praises work over leisure, when even having a job is considered a privilege. Active non-engagement in the workplace through simulation may be more common than we think. French psychoanalyst and economist Corinne Maier wrote a cynical but humorous book Hello Laziness (which has now been translated into 24 languages) as an attempt to show that hard work in early 21st century metropolitan France does not pay off. The commotion caused by this call for mass lethargy proved to be a myopic provocation for the state-owned enterprise where Maier worked, leading to a disciplinary hearing where she was defended by the company’s union.

However, in the eyes of freelance artists who do not have a union to back them, this tongue-in-cheek action is more reserved for blue- and white-collar workers only. It seems that artists embody an ideal type of worker in late capitalism – mostly working flexible hours, receiving low pay and working under precarious conditions. Short-term contracts, no paid sick leave and no security are just some of the conditions they face.

At Obieg, while being busy with the 15th issue, entitled “The Right to Idleness”, the enlarged editorial team was caught off guard by an epidemic that forced the world to stop and stay at home. Just as the team was scouting for contributions on being idle, they found themselves right in the middle of a period when many artists were feeling COVID-crazy and experiencing a need to create, share and be productive in a world that was constantly changing into ever more unknown forms.

The issue was initially supposed to be about peripheries. The Balkans, to be precise. A change in direction to a more acute topic was needed. We kept the notion of the peripheral status of idleness in public discourse, but focused more on the geographical periphery, namely the authors we know personally or have worked with in the past and who come from the countries of the former Yugoslavia and from a post-socialist context. The aim was to inspire dialogue on idleness, between them and others.

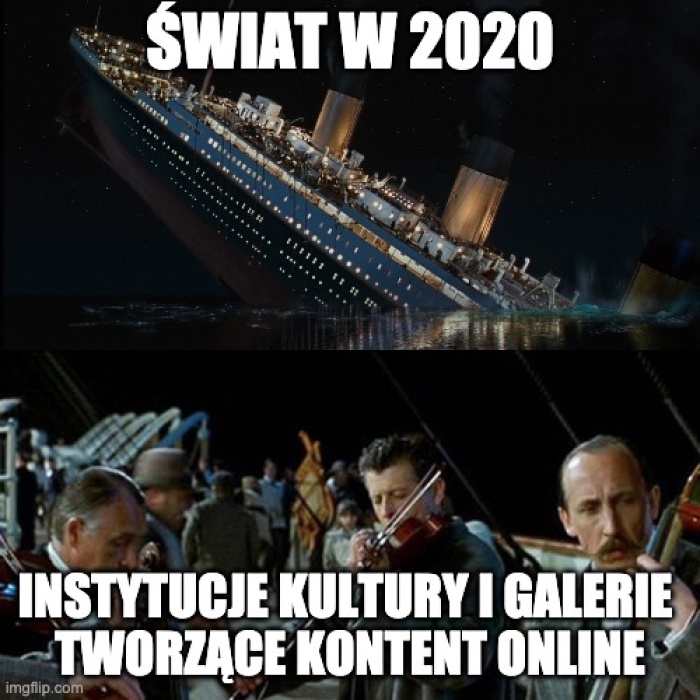

However, we were not busy making the seating order for dinner while the ship was sinking – note the Titanic meme in Obieg’s current section of artists’ interventions (including: bi-, a tentative artist residency, Maja Smrekar, Matt Evans’ and Shinobu Akimoto’s Residency for Artists on Hiatus, as well as Jelena Mijić). The ship in question already started to sink some time ago. In these times of the stand-by mode, we perceive idleness as the carbon paper behind every work: it reveals the social injustice that perpetuates social and class relations that try to obscure hidden forms of exploitation.

So why idleness, and why now? This question came up naturally and echoed around our heads while we witnessed how some artists have insisted on being productive at all costs, even during a pandemic of global proportions. Has the damage of the neoliberal triumph of the past century taught us nothing? Is having a career that can end in burn-out still the best option to make it in the exploitative art world? These were dilemmas that passed through our minds while we tried to justify how timely this issue is.

Being idle is not the same as being lazy; on the contrary, being idle is a part of the work process, even an artistic one. It is work’s most loathed flipside in today’s society – representing its negative side, but not its negation. In Marxist terms, leisure is meant for the reproduction of labor-power. In hyperproductive capitalist societies, time not spent working is considered time wasted.

Work, including its emancipatory impact on self-realization or self-actualization for an individual, becomes additionally drained by society’s needs, especially during times of a pandemic. Throughout the history of mankind, it has been shown that idleness is considered to harm the realm of work, without considering also the benefits it brings (to it).

As mentioned in Bertrand Russell’s 1932 essay In Praise of Idleness, the social order between landowners and workers could be disrupted by idleness. By overcoming the virtuousness of work, Russell argued, idleness could expand the delights of leisure time while reducing exhaustion and still catering for the everyday needs of a modern man. But is the realm of work the right and the only path to reveal social relations, even if we praise idleness not only for pleasure but also, as Russel suggests, for its moral value?

Many answers can be found – and even more questions have been raised – in the interview on idleness and artists’ rights with Milena Dragičević Šešić, cultural policy professor from Belgrade, as well as from the interviewees who commented on the post-COVID-19 situation during the European Capital of Culture (ECoC) – Rijeka 2020. This burning question was also tackled in Marina Tkalčić’s interviews with the protagonists of Rijeka 2020.

The menial labor conditions raised by the pandemic, for the 99% of society that has not been able to escape to exile on yachts or on isolated islands, has shown that the true danger to the social order is more dangerous than some unknown virus. It seems that the pandemic has further highlighted the social structure behind today’s working conditions. And it is not the first time that a pandemic has revealed just how strong the impact on society and (nation) state really is.

In “Contagion and Culpability”, an article by Andrej Pezelj, it is shown how idleness has never been idealized in societies, not even before the 19th century, and how Manichean our perception of crisis really is. The two featured essays, one by Silvio Lorusso and the other by Dorian Batycka, portray the lives of creative professionals in times of lockdown, when life is formed by “forced idleness”.

The generalized yet geo-historically incorrect division between artists in the West and in the East is partly derived from their different status: an artist in the West is considered to be a profession, while in the East it is more of a position. Mladen Stilinović’s Artist at Work shows photos of himself lying on a couch in various positions: recto and verso, but always in the same horizontal pose, as an embodiment of a non-professional stance towards art.

Today’s antipode would be Tomaž Furlan’s cardboard cutout of himself in typical summer attire, entitled Artist is on Vacation!?. The predominant entrepreneurial spirit that represents itself as universal is circumventing idleness for the same reason as neoliberal economists do. The East is becoming less of an exception and acts like a tardy student trying to feverishly catch up on all the missed lessons of his Western counterpart.

Being idle as we show our extensive selection of contributions from many parts of the globe, and from authors offering different perspectives, be it historical, artistic, worker’s or academic, is very different to being out of work. If we can imagine a future after capitalism, we might start to consider idleness a necessity, and not a privilege for the few.

Idleness simply embodies life outside of work, purpose or function. It resembles an existence that operates without moving while the engine keeps still running. The poor man’s idleness offers praise to one’s existence, without exchanging idle time for any other currency, time or goods, with well-being as a goal in itself, and not as an economy's by-product.

BIO

Dare Pejić works as a publicist and a producer, with a study background in sociology of culture, cultural policies and arts management (University of Ljubljana, UNESCO Chair at University of Arts in Belgrade, University Lumiere in Lyon 2). He collaborates with Ljubljana Digital Media Lab (Ljudmila), and Makery from France. As a freelance cultural worker, he has collaborated with many different organizations from Slovenia and abroad. Dare is a former member of Theremidi Orchestra and believes in generalism.

* Cover photo: Belgrade Raw. Courtesy of the artists.