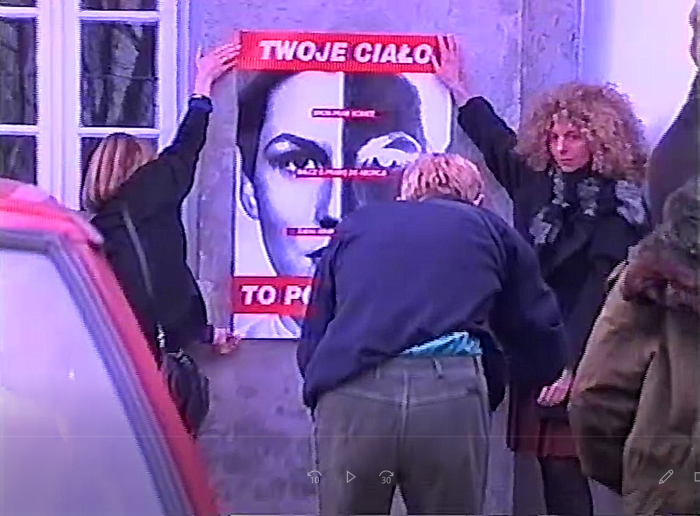

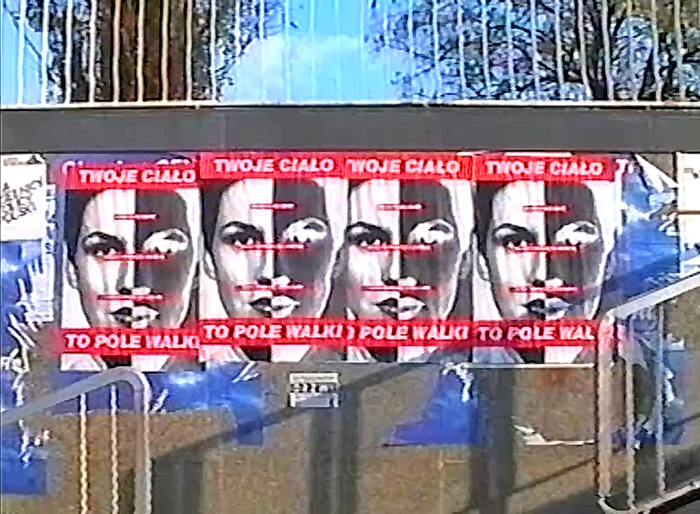

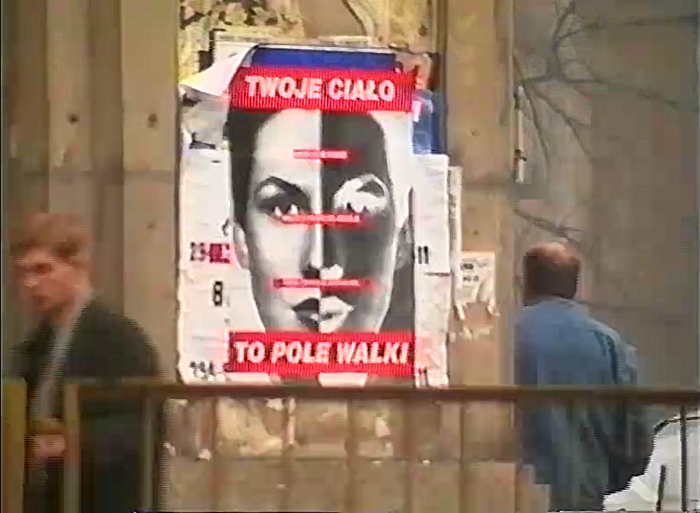

The appearance in 1991on the streets of Warsaw of Barbara Kruger’s pro-abortion poster Bez tytułu. Twoje ciało to pole walki [Untitled. Your body is a battleground][1] is interesting for several reasons. It was one of the first examples of activities at the junction of art and politics after the political transformation. Until then, actions of this kind had been guerrilla and illegal – in this case, a public institution was behind the poster[2]. It was also the first action using public space and advertising media as a forum to present art: in the spring of 1992, the posters were placed on official advertising poles with the involvement of a professional agency. This was long before AMS in Poznań initiated its Outdoor Gallery, presenting on hoardings the works of Polish artists, often also politically involved.

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

Above all, it was the first example of art engaging in a dispute, which, from today’s perspective, can be called the Polish version of the culture war. Until 1989, artists engaging in socio-political issues (there were not many of them) directed their criticism towards the totalitarian system. The front line was between the totalitarian régime and the enslaved society. This front line became anachronous after 1989. Poland and Polish society entered the arena of a broader world-view conflict, of which the dispute over abortion was one of the most-important, if not the most-important, manifestation. A new front line was drawn between a narrower group in society, which defined itself as progressive and modern (but with a high degree of access to the mass media), and broader, more sceptical towards progress in the sphere of morals (in Poland linked to the teaching of the Catholic Church), which soon began to be labelled as retrograde. In the new conflict, the course of which was more and more clearly outlined by the media, and above all by Gazeta Wyborcza[3], there was a reversal of sides in relation to earlier years, which can be seen specifically in the dispute over the anti-abortion law. The communist law from 1956, which allowed abortion for so-called social reasons (in practice, on demand), was defended by progressive circles as democratic and tolerant. In contrast, the demand for a new law restricting abortion on demand was criticised as oppressive and totalitarian.

The Polish version of Barbara Kruger's pro-abortion poster was one of the first artistic weapons used on the newly demarcated front. The posters were imported, as this kind of art did not yet exist in Poland. In the United States the debate had been present for at least two decades. Art had also been engaged on the “progressive” side of the argument, which emerged in the artistic mainstream as a consequence of 60s’ counterculture. The main contributors to this trend included Hans Haacke, Martha Rosler, Krzysztof Wodiczko, and Barbara Kruger.

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

In the 1960s Barbara Kruger was still working as an art director for media companies publishing women’s magazines. In the 1970s she tried to enter the art world, but initially without any significant success.

It was not until she read Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin, theorists promoted by left-oriented academics and art critics, that her path to artistic success was opened up. However, not only theory, but also form was important here. In her work, Barbara Kruger combined her experience in advertising and press design with references to the collages and photomontages of the Soviet avant-garde, especially Alexander Rodchenko (Aleksandr Mikhailovich Rodchenko) and El Lissitzky (Lazar Markovich Lissitzky). The 1960s and 1970s were a period of heightened interest in the Soviet avant-garde by the American art world. In 1972, the influential magazine Art Forum published an extensive text by Alan Birnholz devoted to Lissitzky’s work (El Lissitzky, The Avant-Garde and The Russian Revolution”, Art Forum, 9/1972). A specific nod to the ideals of the Russian avant-garde, but also to the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, was the exodus of a group of critics and art historians from the editorial board of Art Forum, and the founding of a new magazine in 1976 under the title October, in honour of the Great October (i.e. the communist revolution of 1917). This milieu formed the intellectual base of left-oriented artists such as Barbara Kruger.

The Russian avant-garde went from analysing the basic elements of artistic language – colour, shape, line – to politically engaged posters which used the conclusions of this analysis. i.e. from art to propaganda. Barbara Kruger made her way from commercial graphics to ideological art. After 1977, a distinctive style emerged in her work, which consisted of juxtaposing black-and-white photographs from magazines with slogans demonstrating the oppressiveness of the existing social order, placed on a clearly-marked red background. Its simplicity and flamboyance were reminiscent of Soviet propaganda posters. Also, the arrangement of her exhibitions in galleries, where Kruger pasted whole walls of rooms with fragments of photographs and texts on expressive black and red backgrounds, brought to mind the flagship shows of the Soviet avant-garde with the famous Press Exhibition in Cologne in 1928, and El Lissitzky's arrangement. The apogée of her work came in the 1980s, i.e. during the Presidency of Ronald Reagan, when left-wing artists were sounding the alarm against the supposed catastrophe which the administration of the Republican President was expected to bring about (it is impossible to compare this ideological mobilisation with the recently ended term of Donald Trump). The rule of the “new right”, as the ideological base of Ronald Reagan and his administration was called, did not, however, prevent Barbara Kruger from representing the United States at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 1982. At the end of that decade, in 1989, a pro-abortion poster Untitled. Your body is a battleground, was created, as a warning against the “temptations” to outlaw abortion from the new Republican President George Bush, who had just taken charge at the White House.

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

To explain the context of the poster and the protests on which it was based, it is necessary to go back to the 1970s, when the pro-abortion circles achieved significant success, but which was threatened in the late 1980s. Ever since the mid-1960s, riding on the wave of the sexual and moral revolution, the liberal-left American élites have sought to legalise abortion, which was not permitted at that time. As Bernard Nathanson, a gynaecologist, and a leader of the pro-abortion movement at the time, described, this process was carefully premeditated and oriented towards changing public opinion on the issue of killing the unborn. Nathanson worked with the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, founded in 1967, and led by Lawrence Lader. “The manipulation of the media” – Nathanson recalled – “was crucial, but easy with clever public relations, especially a steady drumfire of press releases disclosing the dubious results of surveys and polls that were in effect self-fulfilling prophecies, proclaiming that the American people already did believe what they soon would believe: that all reasonable folk knew that abortion laws had to be liberalized.”[4]

This is not the place to describe in detail this process led by many organisations to induce the public to believe not only that abortion is a woman’s right, but indeed that the denial of this right is a kind of oppression, and a crime. Bernard Nathanson, who, under the influence of the experience of working in the first abortion clinics which he founded, and which he managed in an exemplary way, gradually espoused the conviction[5] that abortion was killing unborn children, included this conclusion in his book entitled The Hand of God. A major role in this change of position was played by ultrasound scans, introduced in hospitals in the late 1960s and early 1970s, first used for foetal diagnosis. Nevertheless, it was at this time that the landmark decision leading to the legalisation of abortion in the United States was made.

In 1973, Jane Roe (actually Norma McCorvey, as this was her real name) sued the State of Texas for failing to provide her with an opportunity to terminate a pregnancy resulting from rape. This trial became a landmark, and went down in history as Roe vs. Wade. The lawyers representing Jane Roe succeeded in getting legitimised a woman’s right to abort her unborn child.

This trial was a milestone in the efforts to legalise abortion in the USA. As a result of the Supreme Court decision of January 1973, abortion was unconditionally permitted up to the 12th week, and, in cases of more-advanced pregnancies, the possibility of certain restrictions was recognised, leaving the matter to the discretion of the State courts. This allowed abortion almost up to the last week of pregnancy. In fact, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to life did not extend to the unborn, because the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which protects the lives of US citizens, was passed earlier than the ban on abortion.

A few years later, Norma McCorvey changed her mind about the case, and revealed that the trial had been built on a false premise, and that she herself had been manipulated. First of all, as she claimed, there had been no rape to form the basis for a potential abortion, and secondly she had become a tool in the hands of lawyers and intelligent ideologues seeking to push through their demands. When she realised the consequences of her lie, she became depressed, and attempted suicide twice. Eventually, she became an activist in the pro-life movement, and published a book entitled Won by Love, which tells the story of her case. Her statement became the basis for an attempt to review the 1973 Supreme Court ruling in 1989. Such hopes were shared by pro-life circles and the next Republican President George H.W. Bush, who began his first and only term in the White House in 1989.

In response to the announcement that the issue would be raised in the Supreme Court, feminist circles called a mass demonstration for 9 April in defence of the 1973 ruling, and marched on the US capital under the banner the March on Washington, referring to the famous 1963 protest called by Martin Luther King[6]. It is to this event that Barbara Kruger’s poster was directly linked. However, curiously, the poster proposed by Kruger to represent the event was not accepted by the organisers[7]. So the artist put up the poster in New York on her own, with the help of her students.

A year later, Milada Ślizińska, the freshly appointed Curator at CCA Ujazdowski Castle, visited Barbara Kruger’s exhibition at the Mary Boone Gallery in New York[8]. The overtone of Kruger’s works seemed to her to be consonant with the criticism of – as she recalls – “the post-Solidarność marriage of Church and authority”. After a meeting and a conversation with the artist, she offered to organise an exhibition at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle. Ultimately, the idea was abandoned, as the CCA did not have adequate exhibition space at its disposal at the time. However, the Curator and the artist decided to transpose Kruger’s poster to the pro-abortion protest to Poland. As well as the Curator, the artist Krzysztof Wodiczko was involved in the development of the Polish version of the poster. The printing of the poster was financed by the Egit Foundation, established by Anda Rottenberg, who was at the time the Director of the Art Department at the Ministry of Culture and Art. The poster campaign ran in Warsaw twice – in November 1991 and in the spring of 1992 – at the initiative of the Polish Feminist Association, when, as the Curator says, it was carried out professionally. The posters were placed at the correct height on advertising poles, thanks to which they were not vandalised.

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

z archiwum CSW Zamek Ujazdowski w Warszawie

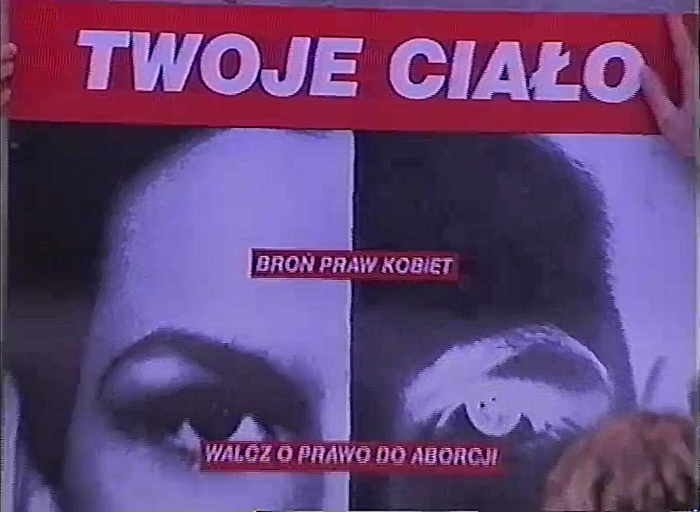

The form of the poster is simple. The main element is a photograph of a young woman’s face framed symmetrically in a close-up from her chin to the top of her forehead. Eyes turned towards the viewer, mouth closed. The axis of symmetry divides the face into two parts: positive and negative. This image is overlaid with inscriptions, printed in white sans-serif verse on red background stripes. The larger one, “YOUR BODY IS A BATTLEGROUND”, broken into two parts, encloses the oval of the face from above and below; three smaller inscriptions on separate strips in the areas of the forehead, eyes, and above the mouth of the figure, “DEFEND WOMEN’S RIGHTS”, “FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO ABORTION”, and “DEMAND SEX EDUCATION”. Unlike in the English-language version, information about the March on Washington in 1989 was missing. The slogan on sex education, which was absent from the first version, was introduced, while the words “birth control” were dropped. On the other hand, the slogan on abortion was strengthened: the original “SUPPORT LEGAL ABORTION” was replaced by “FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO ABORTION”.

The halved black-and-white face of the woman evokes a sense of unease, of danger, which is reinforced by the military verbal layer, calling for a fight, formulating demands, defence. Which way is the front line in this war? Exactly through a woman’s body – as the slogan says – symbolised by a face divided into two. A woman standing in front of the poster can, as if in a mirror, check herself in the depicted face, and observe, with anxiety, first the dividing line running through its centre, and then find confirmation of her observations in the inscription, which is redundant in relation to the visual layer. From the other slogans she can learn what she should do about it. The poster simultaneously declares “There is a war on!” and indicates methods of action.

It is not a traditional war, engaging armies and conventional arsenals. But does this war not involve fatal casualties? Are they women? Both sides of this argument, the pro-abortion side and the pro-life side, both agree that abortion is permissible in cases in which a woman's health or life is at risk. Proclaiming the slogan that the opponents of abortion demand its absolute prohibition is demagogy. However, the potential victims are those who have been removed by abortion – evaporated, to use a term from George Orwell’s famous novel. Evaporated, not killed, because for those who support abortion, the victims never existed, so they cannot be discussed – they are deprived of their future, but also of their past. There is no place for them on Barbara Kruger’s poster either. If, on the other hand, one assumes that the dignity of the person is an inalienable right of the human being from conception, the number of victims has long since exceeded millions. This is the front line in the culture war – it coincides with the frontier of humanity.

[1] The poster is now part of the International Collection of Contemporary Art at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art.

[2] Milada Ślizińska points out that the then Director Wojciech Krukowski distanced himself from the poster campaign, but a meeting with Barbara Kruger was held at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, and Milada Ślizińska herself was a Curator of the Castle, see Plakaty Barbary Kruger zrywano ze ścian niczym zdobycze. Rozmowa z Miladą Ślizińską, Ola Barłożecka [Barbara Kruger’s posters were ripped off the walls like spoils. An interview with Milada Ślizińska], “Magazyn Szum”, 22 January 2021

[3] G. Kucharczyk, Strachy z gazety [Newspaper frights], Fronda, 2011, pp.155-167

[4] Bernard Nathanson, Ręka Boga [The Hand of God], p. 113

[5] It is important to emphasise that Nathanson did not change his conviction about abortion under the influence of religion or the activities of pro-life organisations, which he later joined. And he was not baptised into the Catholic Church until the 1990s.

[6] Molly Yard, head of the National Organisation for Women, which organised the March on Washington in 1989, was specially honoured in 1991 by the French Alliance des Femmes pour la Démocratie for her active promotion of the early-abortion pill RU-486 (manufactured in Paris) in the USA. The Roussel-Uclaf concern, which produces this drug, is part of the German pharmaceutical giant, Hoechst, which is a continuation of I.G.Farben. Zyklon B was produced there during the Second World War, so, to escape bad associations, the name was changed after the war.

[7] Plakaty Barbary Kruger zrywano ze ścian niczym zdobycze. Rozmowa z Miladą Ślizińską, Ola Barłożecka [Barbara Kruger’s posters were ripped off the walls like spoils. Interview with Milada Ślizińska], Magazyn Szum, 22 January 2021]

[8] ibidem