A prominent and time-consistent characteristic of Southeast Asian contemporary art, visible in selected Southeast Asian visual practices from the 1970s onwards, is a conceptual inflection made accessible by suggested or actual viewer involvement in the functioning piece.[i] Works of art, whether a public-inviting installation, or performance in zones of collective traffic, are often structured to include audiences through witness, collaboration, or exchange, in a way reminiscent of games. A second noteworthy feature of Southeast Asian contemporary art emerging in the final decades of the twentieth century, is a critical interest in current social reality. Methodologies of play, and critical interrogations of the world, are linked in Southeast Asian contemporary visual practices as pieces’ participatory modes which allow viewers to grapple with uncomfortable tensions embedded in the artwork in indirect but marking ways. This essay explores why, and by what means, artists in Southeast Asia have continued over more than four decades to produce visual practices that associate conceptual tactics, audience intercession, and social questioning.

Illustrations of the playful genre

An installation such as Indonesian Heri Dono’s (b. 1960) kinetic bowing heads Learning to Say Yes, derived from the artist’s 1990 Fermentation of the Mind, illustrates an aesthetic process combining action and metaphor. Through its mesmerizing nodding movement Learning to Say Yes compels viewers to experience the piece over time. Audience involvement garnered through the prolonged gaze, along with the piece’s ironic title, prompts a questioning of acquiescence to state authority. Similarly, Dono’s set of wayang kulit puppets in the shape of the islands of Indonesia, Wayang Legenda Indonesia Baru of 2000, implies an active viewer spectacle typical of wayang kulit puppetry as the performance piece probes the fracturing of Indonesia in the post-Suharto period.[ii] While these mobile installations are playful and suggest both viewers’ presence and rejoinder, Thai multi-media practitioner Sutee Kunavichayanont’s (b. 1965) pieces are reliant on audiences’ actual physical intervention to communicate their meaning. In the case of much of the artist’s oeuvre, metaphor and concrete intervention are intermeshed to bring abstract and contentious significance to a broad public: Sutee’s audience-inflatable latex/silicone Breath Donation series (1997-2001), and his History Class school-desk installations (various iterations from 2000), discussed later, through viewers’ gestural involvement, seek to foster citizens’ sense of responsibility for the nation’s political destiny. Thailand’s Manit Sriwanichpoom’s (b.1960) Horror in Pink, Singapore multi-media artist Lee Wen’s (b. 1957) Ping-Pong Go Round, Hanoi multidisciplinary artist Vu Dan Tan’s (1946-2009) Fashion cardboard suit series, and Saigon’s Dinh Q. Le’s (b. 1969) tactile The Texture of Memory (2000), employ various types of spectatorship, touch, and play, along with word-games, to draw the public into a querying of power and the status quo.

This emphasis on layered and critical ideas, underpinned by the Southeast Asian work of art’s tangibly working nature that forces audience inclusion, facilitates the communication of abstract notions not easily described pictorially. Complex issues such as the legitimacy of authority, the recovery of lost histories, and the questioning of social and political exclusion, are made relevant to the ordinary public through artistic languages that convey concept through play.

Southeast Asian art’s frequent deployment of conceptual strategies for the sake of social critique is thus fundamentally distinct from Conceptual Art in the Duchampian vein.[iii] Contemporary art in Southeast Asia is a relatively young field of scholarship, but however young, it is apparent that Southeast Asian artists’ penchant for conceptual modes that implicate audiences through play, has evolved largely out of the local context.

Art’s conceptual play and citizen voice

As early as the 1970s-1980s, pioneers of Southeast Asian contemporary Redza Piyadasa (1931-2007) in Malaysia, FX Harsono (b.1949) and Jim Supangkat (b.1949) in Indonesia, Vu Dan Tan in Hanoi, Cheo Chai-Hiang (b.1946), Tang Da Wu (b.1943) and Amanda Heng (b.1951) in Singapore, Chalood Nimsamer (1929-2015), Montien Boonma (1953-2000), and Vasan Sitthiket (b.1957) in Thailand, and Brenda Fajardo (b.1940), Imelda Cajipe-Endaya (b.1949), and Santiago Bose (1949-2002) in the Philippines, among others, produce works that are not art-for-art’s sake, didactically social realist, or exclusively descriptive, but instead weave together disparate semantic and visual codes that interrogate and allude, rather than state. Pieces by these artists call unabashedly on audience response: we see this in FX Harsono’s 1977 rice-cracker pistols and text installation’s viewer-directed question Apa yang Anda Lakukan jika Krupuk ini Adalah Pistol Beneran? (What would you do if these crackers were real pistols?) that viewers answer in writing in the notebook provided by the artist adjacent to his mound of crackers; in Amanda Heng’s communal tea-drinking invitation from 1996 Let’s Chat; in the engineering of audience involvement through material construction displayed in the 1970 piece by Piyadasa May 13, 1969 which includes the viewer-incorporating mirror at the installation’s base; in Philippines multi-media artist Josephine Turalba’s (b. 1965) disturbingly uncomfortable yet beautiful spent bullet-cartridge Scandals (from 2013 and later), slippers that the public wear; and in Vu Dan Tan’s Basket Mask series of the 1970s that in its appropriated basket-mask form, recalls public performance known to all Vietnamese. Such pieces, and many more, no longer passive and self-contained like academic painting, present forms that encourage back-and-forth conversations with viewers about shared issues. As is apparent from the number and geographic distribution of such pieces in Southeast Asia, from the 1970s until today, Southeast Asian artists have continued to use inclusive play as a stratagem to help the public discern the layered concepts supporting their art-pieces. This approach, described as “discursial” by art historian John Clark, is an expressive language designed to awaken audiences’ questioning and interest in matters of collective interest. But this is not query for the sake of banter, nor indeed Relational Aesthetics – which emerges decades later, and does not necessarily possess critical function, – but rather query as a means of proposing alternative outcomes to those instigated by official systems. Encouraging audiences’ critical thinking is therefore a frequent starting point and justification for Southeast Asian conceptual modes. This is explained by Southeast Asia’s dearth, in many places even today, of accepted conduits of individual political voice. In this connection, the ambiguity of oblique communication of ideas that are the constituents of conceptual tactics, beyond a playful appeal to a broad public, in its allusiveness, offers protection from state censorship, the latter still pervasive in much of Southeast Asia. This connection between Southeast Asian art’s conceptual leanings and the region’s constrained political contexts is thus a practical one.

Heri Dono Learning to say Yes Kinetic installation. 1992

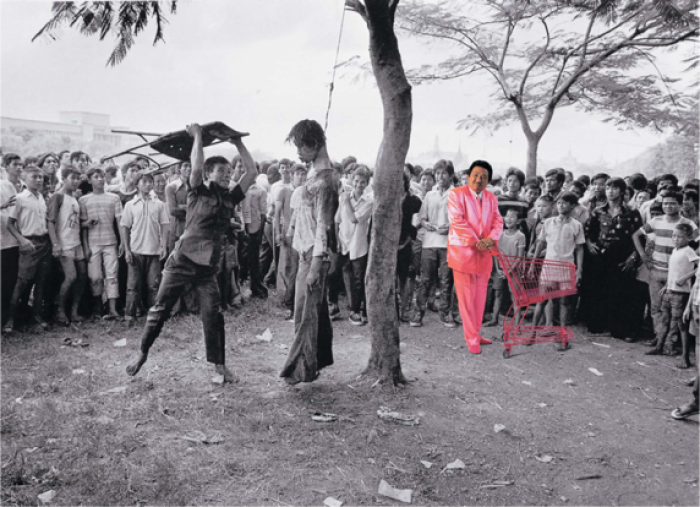

Manit Sriwanichpoom, Horror in Pink, Photographic series based on 1976 press images. 2001 fot. Manit Sriwanichpoom

Lee Wen Ping-Pong Go Round Round ping pong table used by the public. Various iterations from 1998.

Josephine Turalba Scandals Spent–bullet cartridge slippers installation and public wearing and walking performance. Various iterations since 2013. fot. Aras Bankoglu.

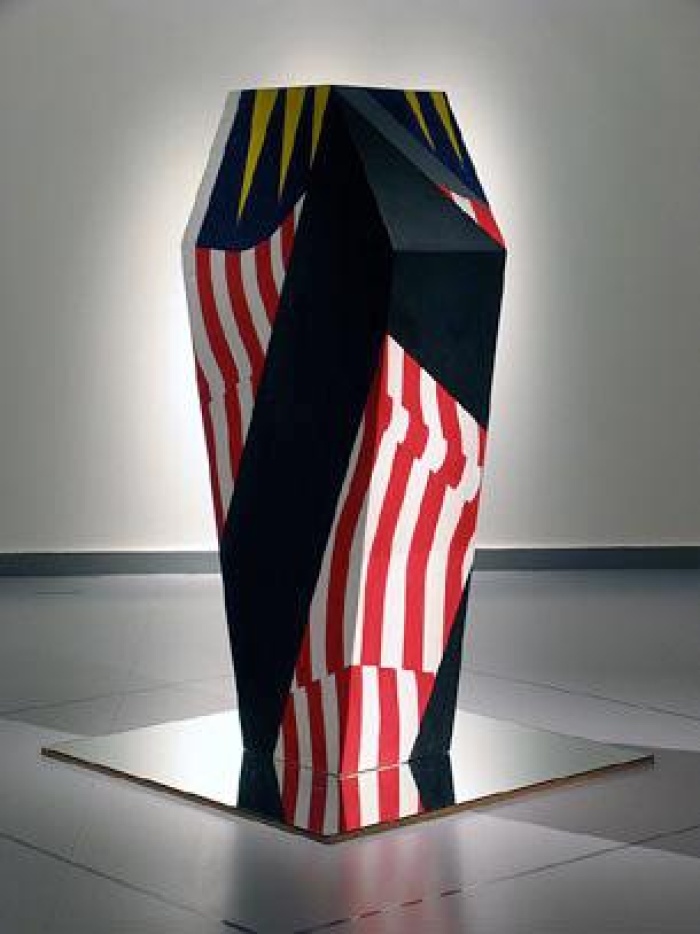

Redza Piyadasa 13 May, 1969 Painted coffin installation with mirror at the base. 1970. Image SINGAPORE ART MUSEUM

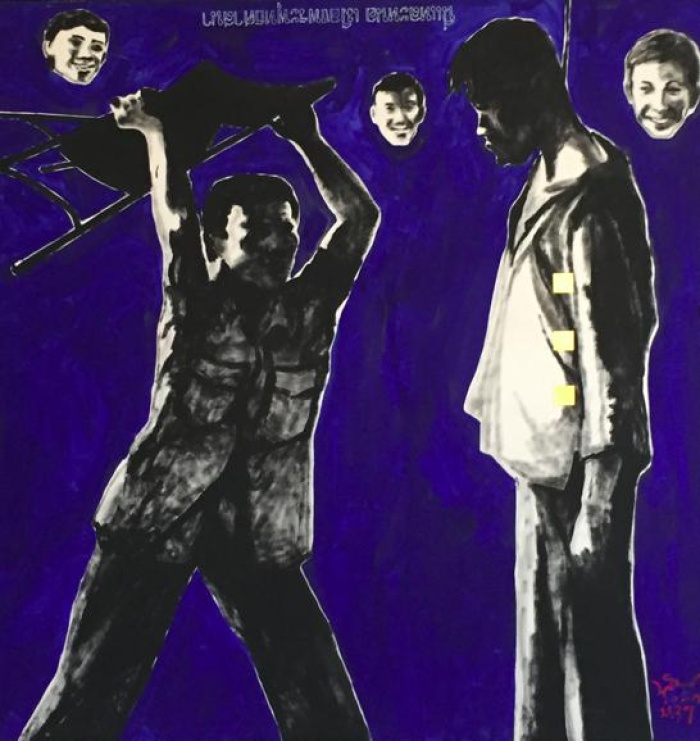

Vasan Sitthiket Blue October Series of 20 paintings, indigo and gold leaf on canvas. 1996.

Chaw Ei Thein (with Rich Streitmatter-Tran and Aung Ko) September Sweetness Outdoor, progressively melting sugar installation in the form of a Burmese temple. 2008 fot. Chaw Ei Thein

Chaw Ei Thein (with Rich Streitmatter-Tran and Aung Ko) September Sweetness Outdoor, progressively melting sugar installation in the form of a Burmese temple. 2008 fot. Chaw Ei Thain

Vu Dan Tan Cadillac/Icarus in RienCarNation 1963 Cadillac transformed into an installation and performance. Oakland California and Hanoi, 1999-2000. IMAGES OAKLAND AND HANOI NATALIA KRAEVSKAIA

Vu Dan Tan Cadillac/Icarus in RienCarNation 1963 Cadillac transformed into an installation and performance. Oakland California and Hanoi, 1999-2000. IMAGES OAKLAND AND HANOI NATALIA KRAEVSKAIA

Sutee Kunavichayanont History Class (Thanon Ratchadamnoen), 2000 IMAGE SUTEE KUNAVICHAYANONT

History Class Part 2, 2013 Used children’s school desks engraved with scenes from history and other references to history; paper and pencils for producing rubbings then belonging to viewers.

History Class Part 2, 2013 Used children’s school desks engraved with scenes from history and other references to history; paper and pencils for producing rubbings then belonging to viewers.

Amanda Heng Let’s Chat Tea-drinking and been-tailing performance with the public. Various iterations since 1996.

Amanda Heng Let’s Chat Tea-drinking and been-tailing performance with the public. Various iterations since 1996.

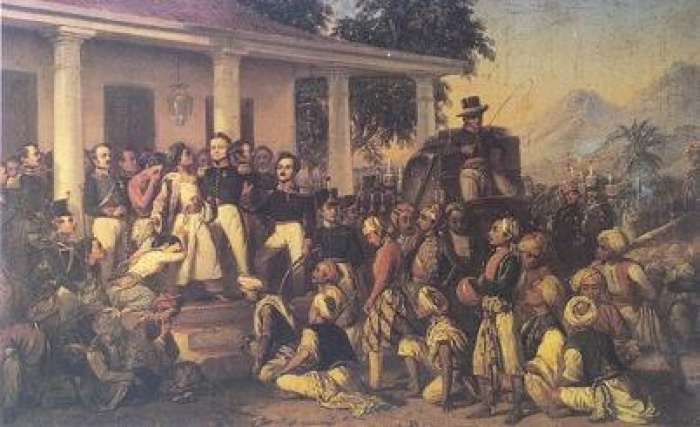

Raden Saleh (circa 1811–1880),Penangkapan Diponegoro, Depicts the arrest of prince Diponegoro at the end of the Javan War (1835-1830), 1857 Źrodło/Source: Wikipedia

Conceptual strategies as expansion from, rather than reaction against, academic practice

Unlike Conceptual Art emerging in Euro-American centers in the twentieth century offering a reflexive critique of the art world’s practices and institutions, conceptual tactics in Southeast Asian art from the nation-building era onwards, are linked to Southeast Asian artists’ expanding view of art’s outward-gazing social function. As the 1970s dawned, the region’s bigger socio-political picture, rather than art-world workings, drew many Southeast Asian artists’ critical attention. These artists then conceived of practices that grappled with a changing society and its tensions. And even when artists assailed art platforms and structures, it was not necessarily for the sake of ambushing these proper. Instead, artists attacked art systems (such as art-teaching institutions and state-run art competitions[iv]) because they saw them as embodying residual colonial attitudes to culture, or with repressive political regimes. As artists expanded from conventional methods and themes (oil on canvas; representational genres etc.) inculcated by conservatively-run art schools that often reinforced state discourses of authority – they gravitated to conceptual languages even as they recalled Southeast Asian material culture’s place at the heart of everyday life. Visual practitioners were not restricted by essentialist ideas of local artistic languages, but sometimes used these familiar forms when helpful for translating abstract notions. People-integrating, audience-actioning methodologies reminiscent of play were part of this home-based expression.

Conceptual approaches, social change, and formal languages

As artists moved beyond orthodox art school conventions of representation they not only experimented with form and theme, but also with art’s function and reach. Visual practitioners imbibed the essence of the times to focus on the energy, upheaval, and unprecedented promise of shift and potential progress offered by rapid and convulsive social change. The catalysts for artistic revolution came at least partially from beyond the art world as social and economic transformation created new aspirations and vulnerabilities all over Southeast Asia. From the 1970s onwards democracy lobbies gained traction in Thailand, even as government repression frequently countered citizens’ attempts at political emancipation.[v] In 1986, Vietnam’s Communist government initiated doi moi economic reforms that irreversibly altered the nation’s social fabric. Indonesia’s liberalizing financial policies of the 1980s helped the dynamics of dissent that eventually toppled the Suharto regime in 1998. And in 1986, in the Philippines, the country’s People Power movement showed the potency of the collective for enacting political change as the brutal Marcos dictatorship was overthrown. In this late Cold War period, the empowerment of ordinary citizens was a tantalizing possibility that favored experimentation as artists looked beyond art school rules that perpetuated academic precepts grounded in often outdated Euro-American discourses.[vi] Steering out from the academy’s formal and thematic teachings, Southeast Asian artists thus sought alternative intellectual and processual anchors for their art, a concept-based expression responding to new social realities.

True to Southeast Asia’s syncretic tradition, as creators searched for new languages, they did not discard the old, and indeed reclaimed idioms forgotten under the influence of the imported colonial art school. This did not result in anachronism or a nostalgia-fueled revival of village iconographies, now appealingly proto-exotic for newly urbanized Southeast Asians, and in some cases, attractive to the international art market too. Instead, borrowings were sophisticated and selective, and as art integrated social function and activated audiences, aesthetics, and parochial media and techniques were co-opted and adapted to serve the concept in the same way that a familiar grammar supports the learning of new vocabulary.

Vasan Sittkhiket’s 1996 twenty-painting Blue October series commemorates one of modern Thailand’s most demented episodes of state-sponsored violence, the 1976 Thammasat University student massacre.[vii] But Vasan has not simply painted the victims. Instead, he has appropriated the black and white images from October 1976 foreign newspaper reports documenting the incident, then reproduced assailants and victims in large-scale and devoid of background detail. This minimalist pictorial treatment, combined with the semblance of neutrality derived from the press-recorded history that is the paintings’ referential source, gives the canvases a terrifyingly remote iciness. This frigidity is underscored by Vasan’s use of the purest, luminous blue, concocted with natural indigo suspended in medium, and warmed sporadically with the addition of gold-leaf, badges of merit apposed to the victims. Thus, Vasan produces tangible evidence of the massacre, while also provoking a response of cold detachment in the viewer, contradicting initial pathos. The series honors the dead but is also equivocal, the sincerity of facile pathos challenged by the artist’s questioning of citizens’ commitment to the lessons of history. This challenge is further heightened by the ironic titles inscribed on each painting in upside down lettering “This is the Buddism country,”(sic) and “For the state security,” for example, that defy audience passivity as each viewer must work to read the reversed words. Vasan’s image-borrowing, re-contextualization of a Buddhist symbol of merit in the form of the gold-leaf badges, and wordplay, are the series’ conceptual prompts which facilitate Blue October’s interrogation of memory, history, morality, and responsibility. Blue October, far more than representing a historic massacre, plays on conceptual and literal registers simultaneously, so delivering not just the graphic horror of brutality, but the deeper and more insidious violence of Thailand’s repressed historical memory.[viii]

Works of Southeast Asian art that employ conceptual means to raise societal and political issues often address plural audiences located outside the institutional space. In collaboration with collective sites, Southeast Asians use their well-entrenched command of form, and rethink materials – which are capitalized on for their suggestive qualities rather than de-considered as can be the case in Euro-American Conceptual Art, – to produce pieces as visually and sensorially audience-engaging as they are critical. Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan’s 2007-2008 Address, a room-sized cube of foreign-worker chattels and clothing; Chaw Ei Thein’s (b. 1969) September Sweetness of 2008 (with Rich Streitmatter-Tran and Aung Ko), a time-evolving, outdoor installation of a dissolving sugar pagoda decrying Burmese state violence in the face of peaceful civilian demonstrations; Vu Dan Tan’s performative RienCarNation (1999-2000) Cadillac that in its supposed drive through Hanoi streets, aimed to scrutinize the critical intersection of history and globalization in turn-of-the-millennium Hanoi;[ix] FX Harsono’s outdoor performance Burned Victims (1998) recalling then recent racial violence in Java; Nguyen Van Cuong’s (b. 1972) 80-vase audience-engrossing narrative of dystopian Hanoi daily-life Porcelain Diary (1999-2001); Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s (b. 1957) Thai Medley (2002) sung performance to cadavers in a morgue humanizing and individualizing excluded people on the margins of Thai society; and Montien Boonma’s (1953-2000) Venus of Bangkok (1991-93) examining urban decay and alienation, to name some of the most iconic, impart layered, socially-critical ideas through non-art school materials, shared space, and multidisciplinary genres. These pieces, unconventional as they are, speak all the better to ordinary, non-elite Southeast Asians due to their involving character. Where art pieces do not integrate audiences bodily into their sphere through eliciting physical action, their visual/sensual pull via familiar vernacular media (porcelain; textiles; construction detritus), signs (the pagoda; fire), and disciplines (singing; driving; dancing), co-opt viewers through playful forms or iconographies.

Art historical antecedents of Southeast Asian art’s subversion of codes and imagery

The pioneers of Southeast Asian contemporary art can look to regional artistic tradition for an interest in everyday life and society, and antecedents of conceptual methodologies linked to emancipation and contestation. In the 1970s the region already boasts a modern practice allying art and life. Selected Southeast Asian visual artists of the first half of the twentieth century are socially-progressive, their paintings defending social and nationalistic ideals, particularly acute in the late colonial period. Sudjojono and Hendra in Indonesia, Juan Luna in the Philippines, Nguyen Phanh Chanh in Hanoi, among others, put painting at the service of a non-idealized view of ordinary life and the people. Traveling back further in time, one discovers in the oeuvre of Javanese painter Raden Saleh (1811-1880) the association of painting, political contestation, and playful “distortions” of visual codes anticipating later conceptual approaches. Raden Saleh’s Arrest of Diponegoro of 1857, in its choice of pictorial devices and layering of meaning, displays allusive strategies of critique that resemble the visual and semantic play of Southeast Asian contemporary art more than a century later.

Raden Saleh’s Arrest, described as proto-nationalist by scholar Werner Kraus in his 2005 analysis of the painting, is interpreted as a conduit of dissent pointed at the Dutch colonial administration that took over Java in 1830.[x] Though superficially a history painting, Saleh’s Arrest is not didactic in the genre of history painting or social realism. Subtler than these genres, Saleh’s canvas employs cryptic iconological references to engage in Javanese resistance against the Dutch by providing a discreet sense of empowerment to his compatriots. Saleh goes about this by appropriating and reworking a 1830 oil painting by Dutch history painter Nicolaas Pieneman picturing the Dutch triumph over the Javanese at the end of the Java War. The Javanese painter retains much of Pieneman’s academic canvas’ attributes, including its grand scale (Saleh’s version is larger), subject, basic composition, and palette. But Saleh’s picture adulterates Pieneman’s original’s title and pictography to undermine the earlier painting’s imperialistic message. Saleh achieves this through his incorporation of iconographies garnered from the local Javanese cultural repertoire: Saleh’s depiction of the Dutch officials arresting the Indonesian rebel leader Diponegoro reveals the Dutchmen with enlarged, grotesque heads derived from Javanese mythological representation. Saleh’s iconological subversion clearly conveys critical meaning to Javanese audiences, who from this reference would understand the painting’s rebellious ideas. The tweaked title of the work, the Dutch painter’s “subjugation” evoking Dutch domination of the humiliated Javanese, transformed by Saleh into the less passive “arrest,” is also a clue. The Arrest of Diponegoro shows Raden Saleh using an allusive and playful deformations to implant contentious information legible to Javanese but not to Dutch audiences ignorant of Javanese mythology’s pictorial codes. Saleh’s artistic strategy is based on inferred idea, and his Javanese viewers’ willingness and ability to “play” along with his vernacular-sourced meanings suggesting dissent through non-descriptive means. The day’s political context, its effect on national pride, and a will to be heard in an oppressive environment, as opposed to formal experimentation for its own sake, had propelled Raden Saleh onto new expressive terrain led by concept and in alliance with audience. We therefore recognize in Saleh’s Arrest a sophisticated work of art developing social bite through its combination of known pictorial image (borrowed from Pieneman), nineteenth-century Javanese history, familiar mythology, and local audiences’ ability to “read” this playful creative juxtaposition yielding new meaning.

Conceptual tactics and reception

Socially-interrogating art naturally courts reception, aiming to dialogue with wide audiences to prompt thought and reaction. In Southeast Asia’s late twentieth century environment of uncertainty and expansion, artists no longer envisage their production as static, self-contained, and separate from the public. The visual and material remain, but time, space, voids, the immaterial, exchange, movement and the body, are envisaged as additional artistic building materials. These extra “materials” are useful for constructing pieces with new formal and methodological typologies generated by the need to debate the multiple truths and abstract ideas that now compose the everyday. Function and form, life and art, collaborate to shape active artworks. As we have seen, practices often deliver these different vocations and ethos through participative mechanisms that collaborate to bring the public into the artwork’s sphere of ideas.

Conceptual language, as well as enabling the expression of complexity outside representation, shrouds subversive intention, so has the added advantage of confusing the censors. Conceptual tactics are thus sometimes deliberately enrolled for camouflaging socially-provocative ideas. In the moving social contexts of the post-1970s, art has agency, and this agency is made more effective by relying on audiences to operate artworks bodily. Art receivers’ roles are expanded as the public metamorphose from passive spectators to critically-functioning players. Involving audiences physically achieves two ends: firstly, it communicates alternative and potentially dissenting ideas about the status quo to viewers through experience. Secondly, by enlisting the public to join the production process of socio-politically questioning artworks, artists share the responsibility of critique with others, so counter authority’s ability to single out a single subversive offender. In essence then, playfully participative artworks create alliances between citizens and artists who together are empowered to bypass state structures of authority. Thus, certain artworks make no sense without the activating viewer: Sutee Kunavichayanont’s late 1990s inflatable latex installations are illegible without the public’s breath donation; FX Harsono’s previously mentioned pile of rice cracker guns What would you do if these crackers were real pistols? is only complete with the inclusion of the public’s written answers to Harsono’s question. Vietnamese multi-media artist Bui Cong Khan’s (b. 1972) 2010 The Past Moved presents the abstract notion of anticipated nostalgia as tool of contestation. Intangible as is this idea, the artist materializes it concretely as viewers penetrate his mock photo-studio for a photo-taking experience. The work is accessible for its playful invitation, yet is also grounded by serious and dissenting ideas about modest folks’ urban displacement and New Vietnam’s capitalist agenda that marginalizes many. Much performance is only effective through the participation of an energy-refracting public, and installation pieces are frequently mute without the audience involvement shaped as “play” integral to their design.

It should be noted that although the participatory mechanisms of contemporary Southeast Asian artworks mark an innovating expansion from academic modern painting, the artist-audience pact is not in itself a novelty in the historical cultural context of Southeast Asia. Pre-modern artistic expression is rife with forms revolving around a mobile, contributing public – lay and sacred ritual, puppetry of all kinds, Cheo theatre etc. Contemporary Southeast Asian art’s emphasis on reception, meshed with layered and abstract ideas, is therefore not intimidating to ordinary viewers who know little about about art. This is important as it signifies that however seemingly avant-garde the participative installation and performance art of Southeast Asia in relation to conventional representation painting, audiences from all walks of life can make sense of new modes of visual art thanks to its incorporation of familiar processes known in traditional culture.

Bangkok artist Sutee Kunavichayanont’s practice from the middle-1990s onwards illustrates the way in which social query, viewer play, familiar materials and media, and location are allied to create accessible but thought-awakening conceptual works of art. Sutee’s pieces answer socio-political and cultural imperatives, the tension opposing nationalism and individual freedom a particular focus. Form and expressive language develop around concept, the public’s action indispensable to legibility and function. Among the most iconic of Sutee’s audience-centric pieces is History Class and its iterations, begun with History Class (Thanon Ratchadamnoen) in 2000. Composed of children’s desks, the installation easily calls upon the participants’ harboring nostalgia for their childhood schoolroom.

Expanding meaning through material, technique, and the public’s attraction to active play, Sutee’s opting for wooden desks as his canvas is not anodyne. Recognizable to audiences everywhere, the worn wooden desks, like all school furniture, bear traces of anonymous carving. But this is not the random scratching of children. Sutee’s chiseled desk imagery instead proposes historical narratives that have been occluded from the official narrative because they are taboo in their manifestation of state violence or abuses of state authority. These scenes do not feature in the school curriculum, yet Sutee dares to inscribe them at the heart of his installation. The artist supplies viewers with paper and pencils to make rubbings from the desk-top engravings. Viewers therefore become complicit in materializing taboo history which they make their own in the form of rubbings on paper. Through these audience-produced rubbings, Sutee prompts his “students” to re-claim their own banished past. In this way through art and play, the artist provokes critical encounters with state power, nationalist ideologies, history and its authorship, and the individual’s right to empowerment shaping the res publica.

Sutee’s choice of medium for History Class, wood-chiseling, permits the artist to revisit village vernacular that as a familiar “low art” craft idiom, facilitates access to his unusual work of art. Thus, History Class ensures physical and intellectual ordinary-audience rapport through recognizable traditions like wood carving and pencil rubbing. Moreover, to build tension that can discreetly disturb, History Class effects connection between two contradictory notions: the class-room as zone of passive absorption of nationally-sanctioned, and therefore unquestioned ideology; versus the viewer lifting rubbed images, who in interacting with the work, is obliged to think critically. The installation’s examination of the place and substance of history in contemporary Thailand is therefore made visible to wide audiences via a carefully-chosen array of locally-relevant signifiers and processes absorbed thanks to the public’s “play-like” participation. Sutee’s History Class is thus notable as an examples of Southeast Asian contemporary art’s idiosyncratic mix of conceptually referenced social critique, materials and genres, and methodologies of play.

Artists across Southeast Asia search for contextually-meaningful icons and codes that used conceptually, pull ordinary local audiences into their art. Beyond this public however, though pieces are born out of home frictions and discourses, Southeast Asian practitioners canvas broader legibility. Amanda Heng’s Let’s Chat is an ongoing participative performance work begun by the Singaporean artist in 1996. It operates in real time to link strangers in conversation around a table, informally drinking tea and tailing bean sprouts. Communication and language have been a preoccupation of Heng for many years, the artist pondering Singapore’s 1979 “Speak Mandarin campaign” and that campaign’s sometimes nefarious influence on Singapore culture. The government initiative, resulting from Singapore’s language standardization policy, is thought to have weakened Chinese-dialect-speaking communities, erased culture, and hindered communication between the generations in Singapore. Through Let’s Chat’s simple and playful form with its roots in everyday domestic activity, the artist brings participants to raise their own questions about exchange, tolerance, minorities, the meaning of community, and individualism far beyond the borders of tiny Singapore. Let’s Chat therefore shows how concept, local context, a questioning attitude, and a construction of engagement, reminiscent of a playful tea party, can speak to the public everywhere.

Southeast Asian contemporary art distinguishes itself on the global stage with its original form and agile use of conceptual strategies emerging from local contexts. Such practices negotiate and answer the times, often actively involving audiences in this negotiation process via playful, game-like invitations to intervention. These cerebral-material tactics, in collusion with audience participation, are also useful for defying state control as art tackles socio-political taboos with conceptual tools’ elliptical grammar that protects from censorship. Close to life and the great shifts that have engulfed Southeast Asia at breakneck pace in the post-colonial, nation-building, and globalizing eras, conceptual visual practices of Southeast Asia, definitively characterize regional contemporary art. With an ethos of play providing geographically and temporally wide accessibility, and through a querying attitude challenging complacency and status quo, Southeast Asian conceptual art is also relevant to audiences beyond Southeast Asian borders.

Iola Lenzi

November 2016

BIO

Iola Lenzi is a Singapore-based art historian, curator and critic of Southeast Asian art. Also trained in law, she takes a synthetic view of Southeast Asian practices analyzed through the lens of Asian culture and history. She has conceptualized numerous institutional exhibitions in Asia and Europe charting Southeast Asian art historical discourses predicated on regional art’s critical dialogue with power, culture and society. In conjunction with these exhibitions, Lenzi has authored/edited research publications which argue the singularizing traits of Southeast Asian art. She teaches “Society and Politics in Asian Art” in the Asian Art Histories MA program of Singapore’s Lasalle-Goldsmiths College of the Arts, and is the author of Museums of Southeast Asia (Thames & Hudson, 2005). Since 2007, Lenzi has acted as director and curator of Laroche Jacquelin Southeast Asian Art Summer Residencies in the Anjou region of rural France. She is currently pursuing doctoral research on early contemporary art in Hanoi at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

[1] First seen in 1970s Malaysia (in the work of Redza Piyadasa), Indonesia, and Hanoi (in the art of Vu Dan Tan). Studied Southeast Asian works are from Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines. On characteristics of Southeast Asian contemporary art, see Iola Lenzi, “Negotiating Home, History and Nation”, in Negotiating Home, History and Nation: two decades of contemporary art in Southeast Asia 1991-2011, edited by Iola Lenzi (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2011) 7-28. Among the earliest installations exhibiting a deliberate prompt of audience involvement for the sake of participative viewer engagement with socio-politically-charged message is Malaysian artist Redza Piyadasa’s May 13, 1969 of 1970, discussed exhaustively in the longer version of this essay.

[2] Indonesia’s rightist President Suharto was toppled by the Indonesian people in 1998, putting an end to three decades of authoritarian rule and ushering in, along with nascent democracy, a period of uncertainty that threatened to fracture the nation due to Indonesia’s fragile ethnic and religious cohesion.

[3] Argued and supported by works from eight countries spanning more than four decades in Iola Lenzi, “Conceptual Strategies in Southeast Asian Art – a local narrative”, in Concept Context Contestation: art and the collective in Southeast Asia, edited by Iola Lenzi (Bangkok: Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 2014) 10-25.

[4] Indonesia’s Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (or GSRB, the New Art Movement) of 1975, that privileged the link between art and society and the members of which took issue with art for art sake promoted as art establishment discourse.

[5] The 6 October, 1976 Thammasat University student massacre is one among many such examples.

[6] The Ecole des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine, established by the French in 1925 in colonial Hanoi for Vietnamese art students, was notoriously anachronistic in its teaching. The school curriculum emphasized 19th century-style academic techniques and themes while ignoring 20th century developments in French and European art such as Dada, Cubism, and Surrealism for example.

[7] On Blue October Iola Lenzi, “Art Warfare: Vasan Sitthiket’s Red Planet”, in Red Planet exhibition catalogue offsight (Jakarta: VWFA and Galeri Nasional Indonesia, 2008) and Lenzi, “Conceptual Strategies”.

[8] When Vasan painted his Blue October series in 1996, the Thammasat University student massacre of 1976 was a taboo topic in Thailand, official histories of the 1990s silent on this event. In recent years however, the incident has become recognised as part of “official” historical narrative. One may surmise therefore that Vasan and other Thai artists referencing 1976 events in their art (Sutee Kunavichayanont and Manit Sriwanichpoom respectively in 2000 and 2001) may have helped “recall” Thammasat, such that the massacre is nown integrated into the acknowledged “official” Thai past.

[9] The Cadillac/Icarus of RienCarNation was not in fact motor-driven through the streets of Hanoi because the 1963 Cadillac’s engine was confiscated by the Vietnamese authorities upon the car’s arrival from California in the port of Haiphong in spring 2000. However, the engineless car was promenaded in Hanoi’s Old Quarter on a flat-bed truck for one evening in May, 2000. The piece then migrated to Gia Lam outside Hanoi where it formed the basis of a multi-artist sound and body movement performance.

[10] Werner Kraus, “Raden Saleh's Interpretation of the Arrest of Diponegoro: an Example of Indonesian proto-nationalist Modernism”, Archipel, vol. 69, Paris, 2005, pp. 259-294.