on the educational function of jokes in contemporary art

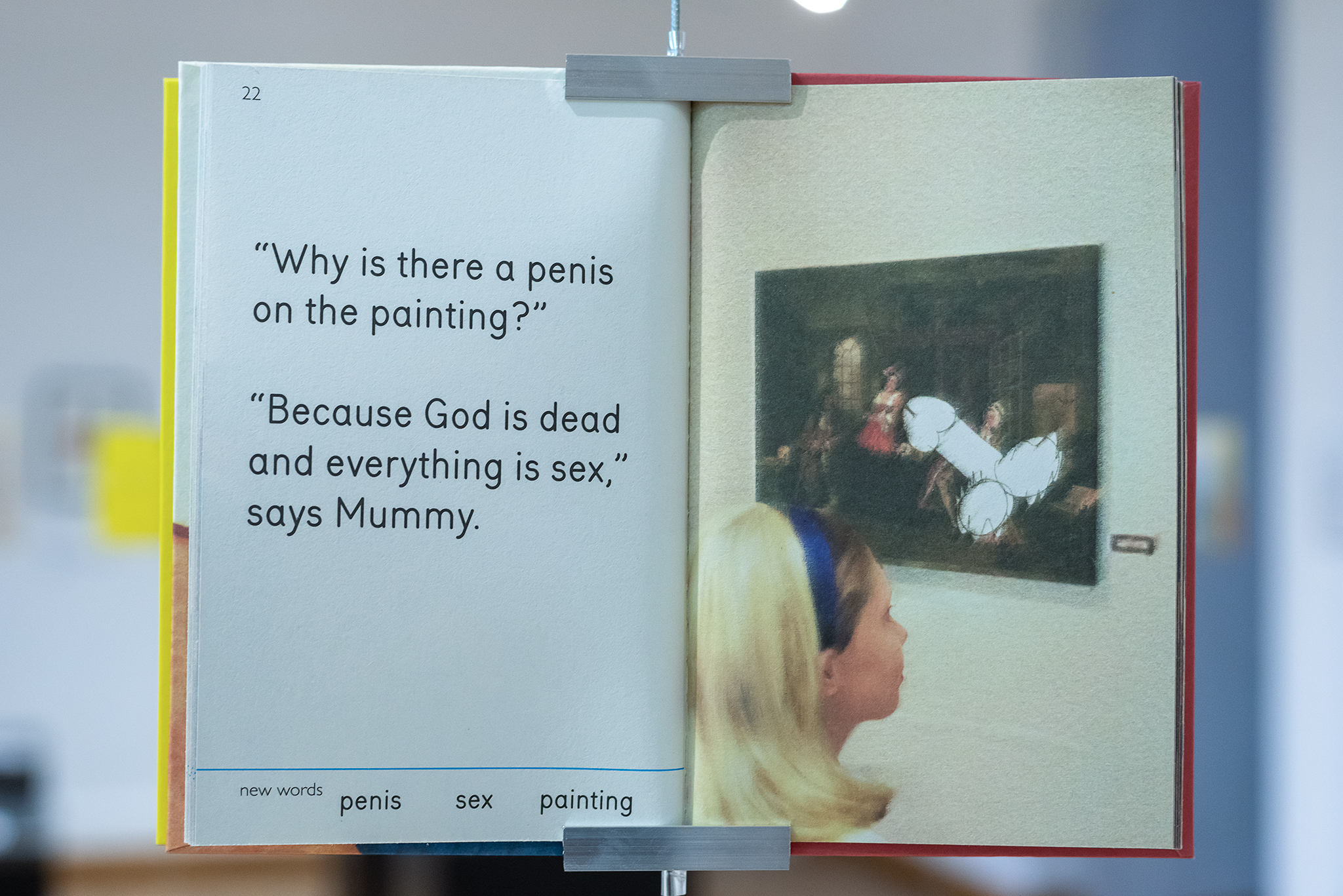

— “Why is there a penis in the picture?”

— “Because God is dead and everything is sex”, says Mommy[1]

When first seen, Miriam Elia’s works give rise to the feeling of slight confusion that quickly turns into amusement. Miniscule books are passed from hand to hand – with finger pointing the extreme examples of mordant wit, slightly absurd at times, but very close to our reality nonetheless. It is the English sense of humour straight from the best Monty Python sketches. Yet, deep inside us there is a lingering feeling that things may not be as funny as they seem…

Wystawa Sztuka polityczna CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot. Daniel Czarnocki

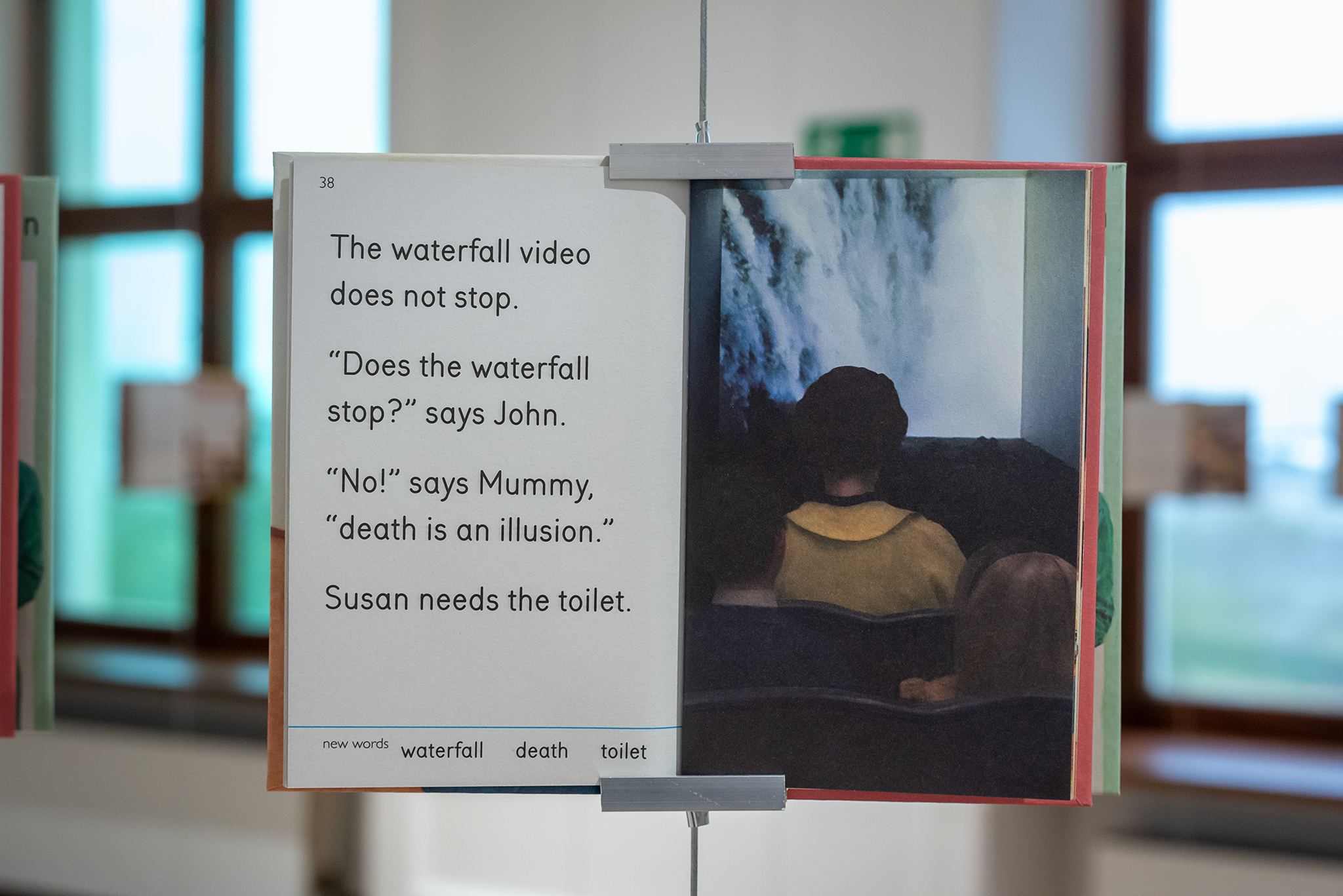

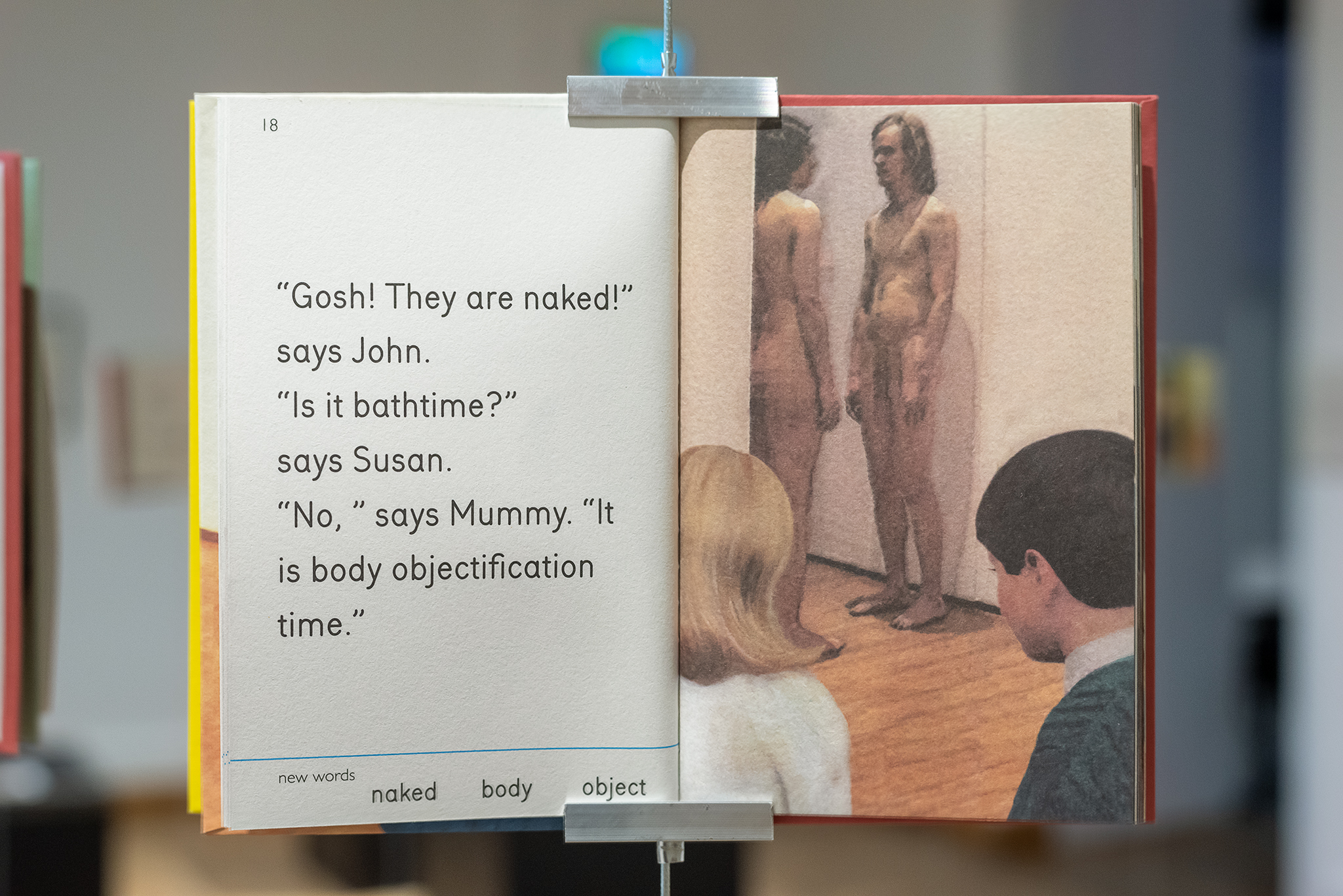

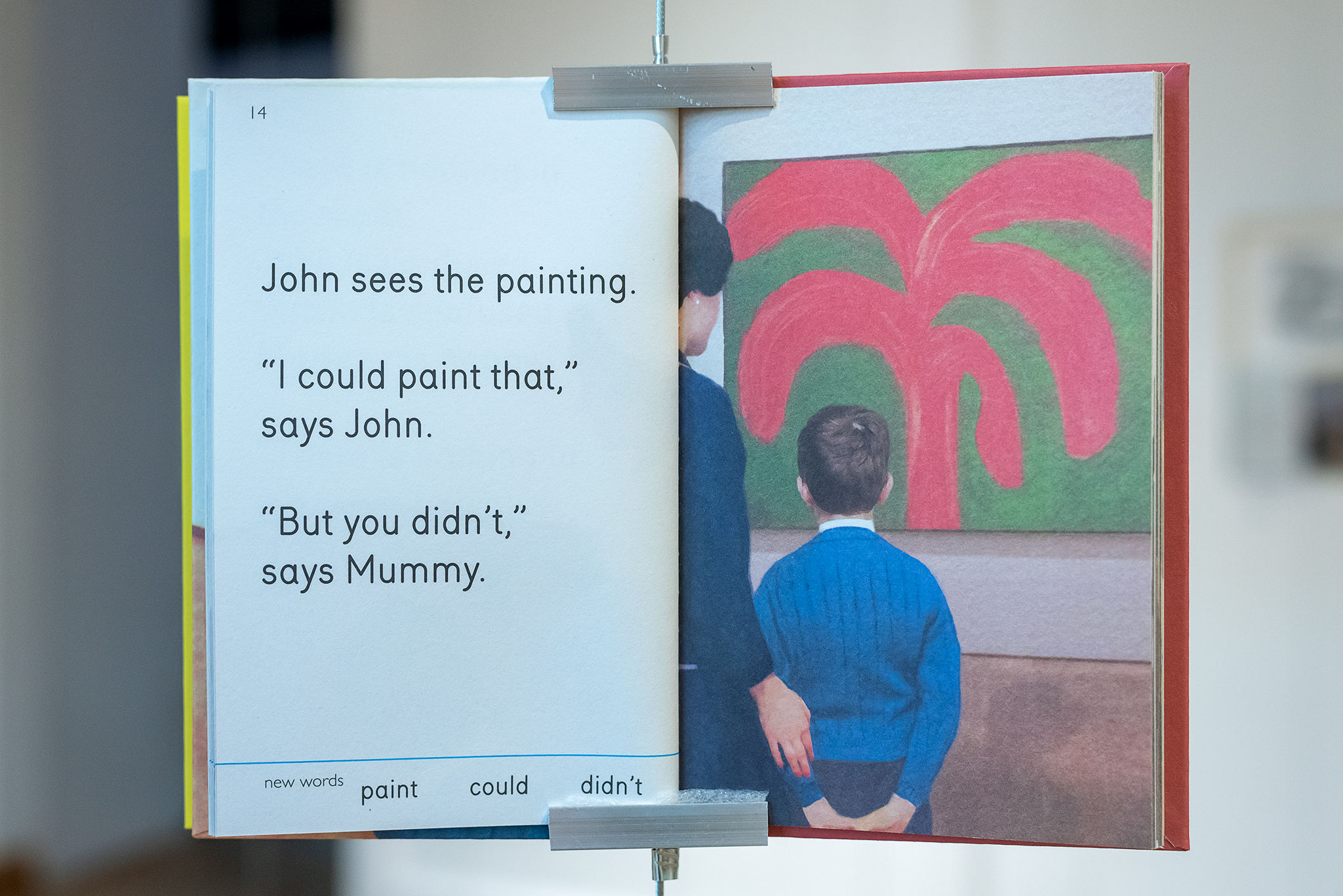

Miriam Elia is a British artist who works in numerous media. She creates short films, animations, book illustrations, radio plays, drawings and more. As we read on the artist’s website, her most famous work is an art book entitled We go the gallery, 1a that Polish audience had an opportunity to see at the Political Art exhibition opened in August 2021 in Ujazdowski Castle Centre For Contemporary Art in Warsaw. The small book (designed together with Miriam’s brother, Ezra) tells a story of three characters – John, Susan and their mom – and their struggle with contemporary art. It opens the “Dung Beetle” series based on cult classic series of publications for children called “Ladybird” by Penguin – iconic books that have brought up generations of Englishmen[2].

In her version, the British artist presents an artwork which adheres close to the original and she also adopts a method of teaching children new words through context, inspired by the “Ladybird” series as well. According to the introduction, “Dung Beetle” publications are intended for children up to five years of age and their aim is to prepare the youngest to function in the society. Learning new words together with John, Susan and their mom is supposed to help „understand basic concepts that children can repeat during elegant dinner parties to impress educated guests”[3].

Wystawa Sztuka polityczna CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot. Daniel Czarnocki

Emphasising education whose purpose is to uncritically adopt concepts related to contemporary art world and ignoring the resistance of child’s mind seeking cause-and-effect relationships reminded me of manipulation mechanisms – specifically those described by the French art historian, Christine Sourgins, in the third chapter of her book Les mirages de l'Art contemporain[4]. She cites there a few of contemporary art “key words”: “baffle”, “embarrass”, “intrigue”, “unnerve”[5] etc. Is there a single soul who, upon entering contemporary art gallery, has not felt as if they were little John from Miriam Elia’s book – not knowing what is it he is looking at, with his mom implying that it is an object to reflect upon? Adopting Sourgins’ point of view, the matter is clear: in most cases, it is not possible to understand contemporary art and its stultifying message distorts our perception of reality in a subtle way. This is how art becomes instrumentalised and used as a tool for social change.

Learning new definitions through the false mirror of contemporary art, as presented in “Dung Beetle”, echoes one of the most fundamental changes that took place in the 20th century philosophy[6]. Namely, it is the linguistic turn, reflected by thinkers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein or Richard Rorty. Accusing those two philosophers of formulating a distorted vision of reality would be as simplistic as occasional allegations that Friedrich Nietzsche is involved in Nazi ideology. Yet, the steps taken by the authors of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature led their successors to the path where the existence of objective truth is negated in favour of its consensual character. Since there is no objective reality, then true is only that which is deemed true by agreement. Language, as an ultimate criterion, becomes a tool for transforming states of things. In this sense, the power to impose specific visions is gained by those subjects who possess an adequate strategy to persuade others (or force them) to accept their arguments. What then becomes one of the chief values is consensus which denies the values of particular debaters. The development of this postulate – on the grounds of sociology – is to be found in works of Serge Moscovici[7]. This French social psychologist observed that minorities have the ability to influence the majority because they are better organised (though often underestimated and disregarded by the majority) and their standpoint is more accurately defined.

Wystawa Sztuka polityczna CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot. Daniel Czarnocki

The above references to the linguistic turn and changes in perceiving reality (also the social one) did not remain exclusively in the academic vacuum. Their influence on the world around us is too evident – a fact that is proven by the black humour of Miriam Elia’s little books. Throughout the entire 20th century[8], with a significant acceleration in the sixties, Western countries were undergoing a revaluation of basic social notions. Nowadays, instead of “institutional power” we have “individual rights”, the “hierarchy” was replaced by “equality”, family – by its various forms, whereas human life was nuanced and is gradually equated with the one of animals and plants[9]. All of this is achieved with cunning manipulations, within the confines of “consensus culture” that most often proves to be typical conformism.

Education reforms appear to have a significant impact on this state of matters as well. A noticeable crisis of the family in Western countries shifts the responsibility of upbringing to schools where social engineering specialists are more and more commonplace, teaching according to new pedagogical perspectives in which the teacher-student hierarchy is replaced with horizontal forms. Child-friendly schools[10] promote various forms of “diversity”, including the ones related to gender identity and sexual orientation. Their activity leads to children and youth losing their stable psychological ground (they are lost in the world, similarly to young characters in Miriam Elia’s books being lost in a contemporary art gallery).

Wystawa Sztuka polityczna CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot. Daniel Czarnocki

In their deconstruction of the old world order, culture revolutionaries are gradually transforming the reality through manipulation and influence on increasingly younger recipients. To achieve such a goal, it is important to lay the foundations for introduced changes. One has to weaken the underpinning of the old ways in order to successfully offer “the new”. Mockery seems to be the ideal means to an end. As described in La haine du monde. Totalitarismes et postmodernite, a book by Chantal Delsol, after the failure of Nazism and the fall of the Berlin Wall, terror became a foul tool to manage the revolution[11]. Ridiculing the opponent proved to be more effective – striking even stronger since it is robed in hypocritical “freedom of speech” disguise. Yet, here one has to remain “revolutionary alert” and know what can be laughed at and what is no laughing matter. Much as scoffing at Christianity is a driving force for many celebrities’ careers (vide Nergal from the metal band called Behemoth and his Never Ending Story in court), Dave Chapelle, a stand-up star, had serious problems after joking about LGBTQ+ movement.

Derision devastates – sometimes more effectively than terror – as a victim is denied their chance of heroic martyrdom[12]. Creating a culture is a daunting task while Pascal’s “thinking reed” can be pulverised by the slightest gust of wind. Mockery utilised by the revolutionary anti-culture comes from the lowest of instincts and is trivially simple. For the young generation, John Paul II is not an author of intellectually stimulating encyclicals, but rather a character from offensive memes – sometimes more, sometimes less insulting, yet most often absurd ones.

Wystawa Sztuka polityczna CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, fot. Daniel Czarnocki

In such a context, Miriam Elia appears to be a critic of anti-culture. To expose instrumental treatment employed by contemporary art, she uses a method of subversion – a mechanism used in contemporary art itself. She mocks (with her usual British charm) the absurdity that we see in galleries and we fear to point it out due to our hesitation towards the institution’s symbolic capital. In the case of the English artist, the irony draws its power from freedom that is built upon standing against the phenomena that one should not laugh at – the new art world “sacrum” and its pseudointellectual pompousness with a caste of “priests” that have monopoly on explaining what particular works mean. It is where anti-ideological attitude of the “Dung Beetle” series manifests, as they ridicule the very thing that ideology forbids to ridicule.

Seemingly trivial measure that Miriam Elia incorporates when creating her works, reveals even deeper layers of surrounding culture to her recipients. The submission of reality to notions, rooted in the instrumentally used linguistic turn, reaches far beyond harmless fun with contemporary art. The gallery space is just one of the places, in many different areas of life, where freedom is taken away from us. Perhaps, this is the reason why, when laughing at Miriam’s jokes, we feel growing concern, deep inside.

English translation by J. Bujno

[1] M. Elia, E. Elia, We go to the gallery, Dung Beetle Ltd., 2017, p. 22, translated by Jakub Bujno.

[2] So far, the artist published five books within the series. Apart from the one analysed in the text, the remaining ones are: We learn at home, 1b (2016), We go out, 1c (2016), We do Christmas, 1d (2018), and We do Lockdown, 2a (2020). To the best of my knowledge, more publications from the “Dung Beetle” series are currently in the works.

[3] M. Elia, E. Elia, op. cit. p. 2 [introduction], translated by Jakub Bujno.

[4] Ch. Sourgins, Les mirages de l'Art contemporain, Paris 2005. In my text, I use the chapter translation published in Artium Quaestiones, see: Idem, Zmagania widza ze sztuką współczesną (translated by Paweł Ignaczak), “Artium Quaestiones” 2010 (21), p. 201-224.

[5] Ibidem, p. 201.

[6] Similar findings can be found in Krzysztof Karoń’s book Historia antykultury. Cf. K. Karoń, Historia antykultury. Podstawy wiedzy społecznej. Wersja robocza, Warsaw 2018, p. 458–462.

[7] I am mainly thinking of a publication entitled Psychologie des minorités actives Cf. S. Moscovici, Psychologie des minorités actives, Paris 1979.

[8] I will not attempt to indicate the historical origins of the state of matters characterized in my text – perhaps I would have to go back to the French Revolution or the famous Martin Luther manifesto, or maybe even further back to the original sin.

[9] Por. M. Peeters, Globalizacja zachodniej rewolucji kulturowej. Kluczowe pojęcia, mechanizmy działania (translated by Grzegorz Grygiel), Warsaw 2010, p. 42.

[10] To learn more on the topic, see: Ibidem, p. 212—214.

[11] Ch. Delsol, Nienawiść do świata. Totalitaryzm i ponowoczesność (translated by Marek Chojnacki), Warsaw 2017, p. 68.

[12] Ibidem, p. 73–74.