Conservatives tend to view contemporary art, or “conceptual art”, as expressions of a failing culture due to a lack of “beauty”. Utterings like “A child could do it better” can often be heard when audiences are introduced to abstract art. Political art can fare even worse. “This is only meant to hurt”, people might say when something they find provocative enters their view. “It’s so poorly executed it’s not even a piece of art at all” is likewise not an unfamiliar linguistic figure in such deliberations. The lack of “beauty” can raise the question of the legitimacy of art in general.

The unforgiving reception of contemporary art may, on the outset, appear as a favoritism of craft. This can be related to this audience’s generally favoritism of tradition, not least traditions upholding the institutions of political freedom, or, in their view, the political status quo.

But in contemporary art the work may not be an object at all. It can be a happening, an experience only carried on in the memories of those who took part in it, and their re-telling of it to others. Or it can be a readymade object from some event that took place. Unawareness on this issue may constitute a threat against the traditional freedoms conservatives considers undermined by contemporary art.

The Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei demonstrates the latter point in several of his works. An obvious example is the work “Straight” (2008-2012), which consists of iron pieces from concrete elements of crumbled buildings. It’s 90 tons of stretched, rusted iron was salvaged from the ruins of a school that collapsed during an earthquake. In the aftermath it was discovered that the buildings suffered from irregular constructions due to corruption. Hundreds of youths died as a result. The government blacked out the scandal from the public sphere. “Straight” travels around the world to tell the truth of what happened.

In the film “The Fake Case” (2013) Ai Weiwei creates a piece even more distanced from craft in the traditional sense. The Chinese state posted agents close to his house to surveil him. At one point in the film he discovers two such men sitting in a dark alley nearby his entrance door. The men hastily depart when the camera team closes in on them, leaving behind an ashtray half-full of cigarette waste. Ai Weiwei collects the ashtray and later presents it as an artwork in an exhibition.

The object – the ashtray – is obviously purely a carrier of a story. The question of aesthetics in terms of craft is somehow not relevant.

Both the ashtray and the steel bars of “Straight” conveys stories of things that took place in reality. They are carriers of truth, confronting the lies of a corrupt political regime. The contrast between the piece’s immaterial properties (the stories they are conveying) and their material properties (the steel or the plastic) is clear to see.

Although political art hardly was on his mind at the time that he wrote it, the English philosopher R. G. Collingwood gives a useful take on this matter in his book “The Principles of Art” (1936).

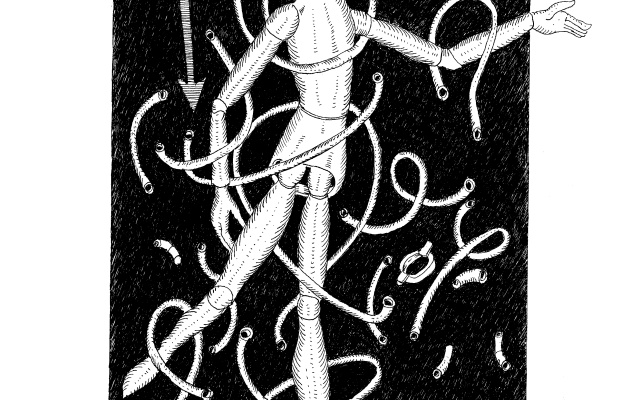

The art work we meet with our senses – a canvas with colors, the tones of horns and strings, letters on pages, etc. – is actually not the artwork itself. Instead these material manifestations can lead us towards the artwork. Which in itself is completely immaterial; it lies, Collingwood explains, in the imagination of the artist. What we call “an artwork” is thus a set of tools that can give us access to the work. The features that we meet with our senses will guide our imagination.

That is: They can lead us in this way if we invest our attention in it. The art work, Collingwood explains, is thus created in a collaboration between the artist and the audience. Our perception of art is an activity that has a stake in the creation of the work we perceive.

Not in just any work of art that comes in our way, of course. But in the works that evokes in us a certain feeling of recognition. Art, Collingwood says, is “symbolic articulation of emotional experiences”. It does not mean that the artist uses art to convey a certain feeling; that would be craft (“communication”).

The artist, on the contrary, discoveres the emotional experience through the making of the work that articulates the feelings. And paves the way for the audience to discover it too. When this happens, the work causes awe and admiration. But not because of its material-aesthetical properties; these can be low-fi or classical. The core of the work will be the experience of truth, or truth-worthiness, in it.

Truth can thus be said to be the ‘beauty’ in art. It does not imply that the artist communicates one particular truth about some topic. It implies truthfulness in the experience itself and in the articulation of it.

Any particular emotional experience is private in a sense. But emotional experiences in general is something we share as living beings. And so, the personal emotional experience has a transcendental aspect, wherein lies a connection between the experiences of the artist and the experiences of members of the audience.

In works like “Straight” the experience of the work’s immaterial properties is different from Collingwood’s idea of the viewer recognizing emotional experiences. Our imagination is led towards other people’s experiences of something that happened in historical time on a certain geographical point. Instead of evoking private emotional experiences the work triggers our knowledge of politics and history and connects us to the experiences of people who lived through a chain of events.

When truth is the beauty one is searching for, the artwork might by simple in its materials and desacralizing (or, for that sake, rude) in its content. It might evoke feelings of anger, or agony, or both. Instead of activating common emotional experiences in the existential sense, the work may confront the viewer’s values, worldviews or faith in authorities. People might seek to destroy the pieces, or at least the artist’s ability to present them (“cancel culture”). The rage said to be caused by a piece of art can in itself convince others, people who even haven’t seen the actual work, that the artist is a dangerous person and (thus) should be “cancelled”, perhaps even punished. Some people with this attitude can diminish even the death of such an artist, saying things like “he asked for it”.

The will to discipline and regulate the artist because of an artwork is often termed as “political correctness”. These emotional reactions can be understood in terms of what Nico Frijdman has described as “the laws of emotion”. One such law, “The law of the lightest load”, dictates that some people are more prone to accept a lie that hurts rather than a truth that hurts even more.

Artists are “called out” and accused of having, or at least expressing, dangerous opinions; or of associating with the wrong kind of friends; or uphold intolerable manners. The factual substance in these cases are always extremely weak. The accusations are usually based on slander. Still they can have dire consequences for those who stand in the receiving end.

Last year a Swedish theater director committed suicide after six months of online shitstorm after he was accused of misbehavior. He was formally cleansed, but the campaign raged on and eventually killed him. Åsa Lindeborg, editor of the main paper Aftonbladet, later regretted her role in the ordeal.

At the end of April this year, the English ballet dancer and choreographer, Liam Scarlett, was found dead only hours after The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen slashed his show, “Frankenstein”. They did so after complaints about the choreographer’s behavior, even though he was also formally aquitted. The show was apparently cancelled out of fear of online attacks on the institution.

In these cases, the art institutions act disproportionately out of fear. They seem to be caught by surprise and instinctively seek cover in “political correctness” instead of confronting the adversary. In the process they embrace a painful delusion (that the accusations against the artist makes it impossible to continue the collaboration) to avoid the even more hurtful lies of an expected online shitstorm.

In this new schisma, rage against art is not caused by the art works themselves but by perceived behavior of individuals connected to the production of an exhibition, a movie, the publishing of a book, screening of a movie, and so on. Attention is drawn away from the art, and artists are instead pulled into malstroms of the social and political life.

Actors in the art world, especially institutions, seems perpetually ambushed and surprised by this kind of attacks. There is a need for a bold rearticulation of the legitimacy of art based on truth rather than beauty in traditional terms of craft. In lack of it, political censorship in the form of “political correctness” will have a sway upon this domain of intellectual freedom. With human suffering, curbing of free speech and subversion of democratic institutions as a result.